Inca Mortuary Practices. Material Accounts of Death in Quebrada De Humahuaca at the Time of the Empire- Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

This contribution has the purpose of presenting a set

of material evidences linked to mortuary practices from Inca times

recovered in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara archaeological

sites. This in order to ponder the role of funerary practices in the

social life of loca populations under Inca control. The presented

contexts refer to diverse practices pointing at the great variability

regarding the treatment of the deceased during Inca times, allowing to

analyze the new socio-political context established in Quebrada de

Humahuaca. The funerary practices registered refer to a strong tradition

linked to the cult to the ancestors, probably rooting from pre-Inca

moments. As in other Andean cases, these manifestations could have

responded to beliefs associated with the regeneration of crops and

productive cycles in general. The role of the deceased in strengthening

the collective memory and the meaning of traditions shared throughout

time is also relevant.

Keywords: Mortuary Practices; Material evidences; Inca domination; Quebrada de Humahuaca

Introduction

The analysis of mortuary practices allows us to

approach several aspects of the societies in which they occurred,

reflecting not only the memory of the group but also the socio-political

and economical processes of it. In the case of the Andes, it has been

stated that the cult to the ancestors has strongly molded the way of

conceiving death and treating the deceased [1-4]. Thus, the body or

parts of the deceased would have functioned as referents of the

ancestor, in charge of keeping the well-being of the community. This

contribution has the purpose of presenting a set of material evidences

associated to mortuary practices from Inca times recovered in the

archaeological sites of Pucara de Tilcara, located in the central sector

of Quebrada de Humahuaca (Jujuy, Argentina), and Esquina de Huajra in

Quebrada’s south-central sector. This, with the objective of analyze the

role of funerary practices in the social life of local populations

under Inca domination. Although being located in the same region and

being contemporaneous, Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara present

characteristics that differentiate them in their spatial and functional

organization as well as mortuary evidences. The presented contexts refer

to a diversity of practices signaling a wide variety in the treatment

of death during the Inca period, allowing us to analyze the new

socio-political context established in Quebrada de Humahuaca.

Quebrada de Humahuaca and the Inca Domination

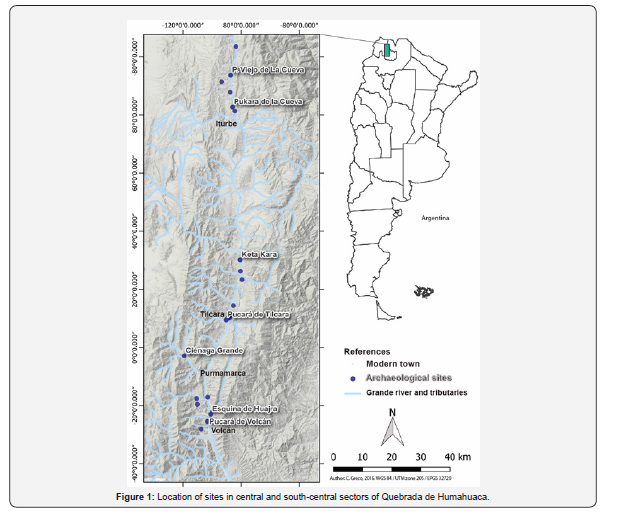

Quebrada de Humahuaca (Figure 1) became part of the

Kollasuyu, the southern province of the Inca Empire, during the first

half of the 15th century. A series of indicators, as the presence of

artifacts and Inca architecture, the network of roads, garrisons and

tambos, refers to this conquest in the Argentine Northwest [5-8].

Williams [6], following González [5], proposed that the Inca political

organization was flexible, presenting notable variations between several

conquered regions, given that imperial administration was built over

pre-existent political systems, making use of an ideology based on

reciprocity and local redistribution of resources in order to legitimate

the newly established economy (Figure 1).

In this sense, the Empire established several

conquest strategies that included both diplomacy and violence, and

strategies of power consolidation, linked to a long process of

integration of the dominated groups. The characteristics of the Inca

occupation in the region depended, as mentioned by Cremonte &

Williams [9], on the degree of political centralization of the ruled

societies and their acceptation or resistance to the domination. The

existence of important settlements both in places with presence of local

population as well as in “empty areas”

would evidence, according to Williams & D’Altroy an occupation

of selective intensity in strategically located productive areas. This

would indicate that the Empire designed its way of government

regarding local situations but always having in mind a largescale

planning, favoring at the same time certain ethnic groups

and using local elites in order to help establish and maintain the

government. The presence of ethnic groups favored above others

would be evidenced by the circulation of certain ceramic styles in

parallel to the Inca Imperial style, as in the case of Yavi Chico, Inca

Pacajes or Inca Paya [6].

The main policies of the Inca government for the conquest of

the South-Central Andes included the installation of fortresses in

the oriental border and the establishment of a vial network, the

installation of imperial centers, the intensification of agriculturalherder

and mining production, and the claim of sacred spaces

by means of the construction of high shrines [6,7,10]. Although

we do not observe a state infrastructure as ambitious as in the

northern regions of the Empire, these policies were executed

by means of sophisticated strategies, as we mentioned before,

adapting themselves to the local variations in each region.

These strategies generated changes in the use and significance

of public, domestic and ceremonial spaces, since they included

military control, ideological claims, demographic relocation,

and agricultural-herding and mining intensification, but also the

ceremonial hospitality and the preferential treatment of certain

conquered groups.

In the Argentine Northwest, the Inca empire created four

provinces, of which the northernmost was Humahuaca, whose

capital would have been constituted in Pucara de Tilcara. Towards

the south, the provinces of Chicoana with its capital in La Paya,

Quire Quire with its political center in Tolombón, and the Southern

province with its center in Tambería of Chilecito would have been located [11]. In Quebrada de Humahuaca, state policies are

visible through the presence of remodeling in the conglomerated

settlements established in the previous period, called Regional

Developments Period (1000-1410/1430 AD). Among these sites

we can identify La Huerta [12-14], Campo Morado [15], Pucara

de Perchel [16], Pucara de Tilcara [17-20] and Pucara de Volcán

[21-24]. Thus, the main administrative centers where established

in most of the pre-Inca sites of the region [12,25]. Remodeling of

previous sites in charge of the state administration would be linked

to the Inca recreation of the conquered community’s landscape,

where architecture could have functioned as a symbolic act of

territory appropriation based on a double-end game of integration

and segregation between the local and the imperial [26,27].

The landscape remodeling performed by the Empire meant

the total or partial abandonment of some sites such as Los

Amarillos [28], reinforcing the changes introduced by Inca

administration in the pre-existent landscape. The case of Los

Amarillos considered as the political center of the Omaguacas

ethnic group [29-34], could indicate, as suggested by Nielsen

[28,35], that the Incas reorganized pre-existent social and power

relations in Quebrada de Humahuaca. As mentioned before,

Pucara de Tilcara would have been the political-administrative

center of the Humahuaca’s province, registering during these

moments the largest occupational density in the settlement,

reaching a complete coverage of the mountaintop where it is

located, of about 17.5 hectares [20]. The findings in Pucara de

Tilcara lead to its consideration as one of the main productive

and administrative poles of the region, in which numerous artisan

workshops destined to specialized manufacture of goods in

metal, shell and stone would have been situated [8]. Likewise, the

possibility of expanding the settlement as well as the proximity to

Alfarcito’s agricultural fields and alabaster, limestone and copper

quarries could have been the main causes behind the Inca’s

usage of Tilcara for the installation of a large productive center.

In addition, the finding of materials with a clear Inca affiliation,

as the Inca Imperial pottery, may account for a state organization

strongly linked with local populations [36]. Among the studied

contexts for this site, we recognized these forms of articulation

mainly within ritual practices involved in the cult to fertility and

the ancestors. Burials and other evidences manifesting different

types of mortuary behaviors express a plurality of events where

social hierarchies within a state political frame could have played

an important role. In other sites of the region, as in the case of

Esquina de Huajra, we also distinguished this variety of practices,

which are exposed below.

Esquina de Huajra

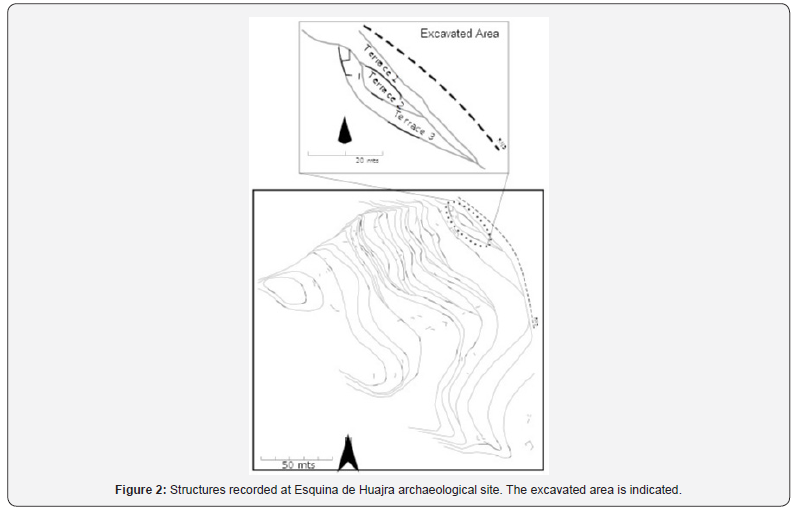

Esquina de Huajra (Figure 2) is a late Humahuaca-Inca

settlement located in the south-central sector of Quebrada de

Humahuaca, in a space not previously occupied by local populations

[26,37,38]. Nine datings obtained in this settlement allowed us to

delimit its occupation to nearly two centuries, encompassing Inca

and Hispanic-Indigenous Periods [39]. Although the occupation of this

site would have lasted until the Hispanic-Indigenous Period,

we have not registered any Spaniard elements. It is a clearly

Humahuaca-Inca context that does not show any of the typical

features characterizing other contemporaneous assemblages,

with clear differences for example, with the cemetery of La Falda

de Tilcara [40,41] (Figure 2).

So far 222 m2 have been excavated in three levels of terraces.

The inferior level, called Terrace 1, corresponds to a domestic

area, probably the patio (external area) of a house where a sector

directly destined to food preparation, storage and consumption

would have existed, associated with a hearth, grinding tools,

camelid remains and fragments of different vessels, as well as

tableware. The presence of a spindle with its whorl is an indicator

of textile activities, while the obsidian cores and flakes point to

reduction tasks for the obtainment of lithic instruments. The

incidence of foreign ceramic pieces in this terrace is remarkable,

especially from the highlands, as well as the deployment of forms,

surface treatment and finish, and fine pastes in tableware. These

elements, added to the presence of polished aribalos (typical

Inca vessel used to store alcoholic beverages such as chicha) and

standing pots, would refer to a context of status and interaction,

allowing us to suggest that Esquina de Huajra functioned as a

strategical and special settlement. The intermediate level, called

Terrace 2, presents a few contention walls and its excavation did

not allowed the identification of a clear occupational floor. Finally,

Terrace 3 conforms a burial area, where we found the funerary

contexts analyzed in this opportunity.

The funerary contexts in Terrace 3

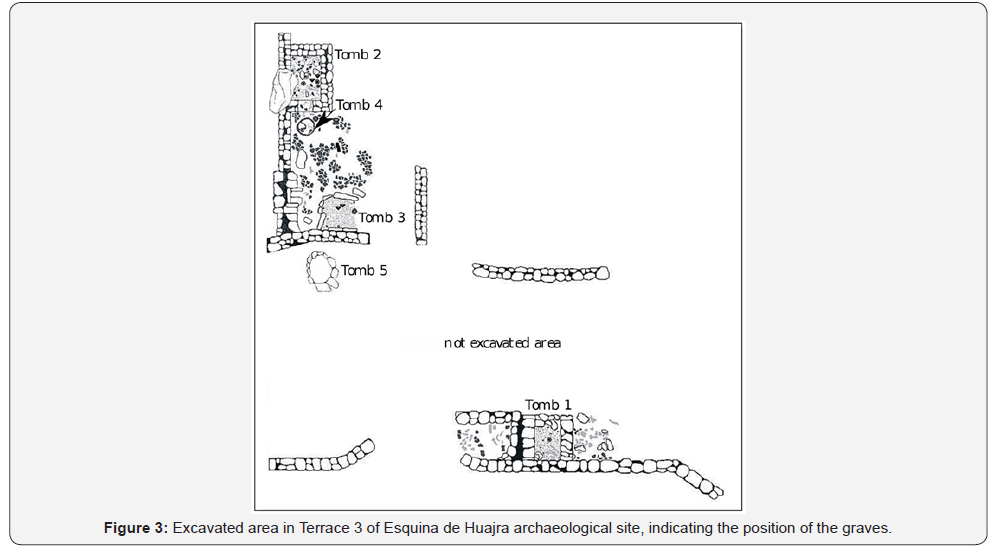

Until now, four burials have been excavated in Terrace 3, as

well as a sector outside the graves (Figure 3). In this space, we

have recovered fragments of polished dishes, plates and bowls

with and without decoration, associated to pots, aribalos, jugs and

jars both ordinary and decorated with local and non-local styles.

At least five large ordinary restricted vessels were registered,

probably used for moving beverages such as chicha and solid or

semi-solid aliments from the domestic units. These vessels were

associated to metal and stone instruments, flakes and three likely

lithic ornaments, among which a mica plate with a central orifice

stands out (Figure 3).

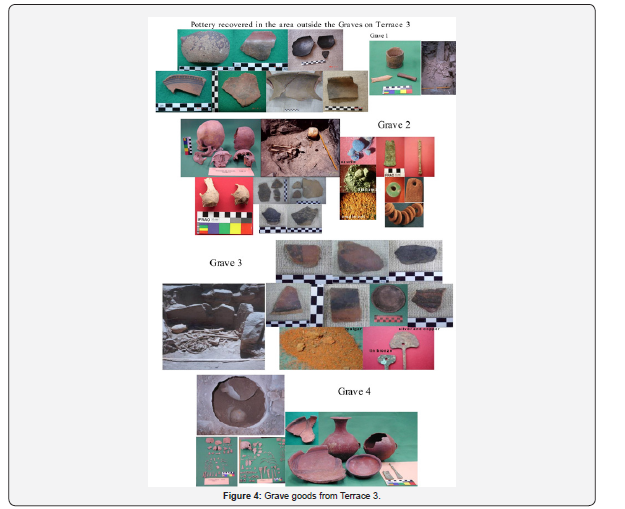

In the external area, polished bowls are more abundant that

within the domestic area (Terrace 1), indicating the individual

consumption of liquid aliments. Little plates, also more abundant

and varying regarding shape and decoration, would indicate a

similar behavior but for the case of solid aliments. Preparation

and storage vessels appeared in less quantity and variety that

inside the domestic area, especially in the case of pots. The better

finishing of vessels and the larger proportion of decorated pieces

in this sector would indicate that, for its use in this sector, people

selected the local pieces with better termination. These evidences

allow us to suggest that the sector external to the graves could

have been an area where individuals could congregate for the

preparation of burials and the corresponding funerary rituals

(Figure 4). The scarcity of preparation and storage vessels

reinforce this idea, indicating the non-domestic functionality of

this sector. Given the fact that we are referencing a reduced space,

we consider that the sector external to the graves could have

reunited a small number of individuals directly participating on

funerary rites (Figure 4).

The graves exhibit variations regarding constructive

techniques, burial modalities and mortuary goods. Tomb 1 is a rectangular chamber constructed over the surface containing the

remains of four adult individuals and a perinatal, conforming a

secondary burial (Figure 4). The grave goods consisted on a small

ceramic vase and ordinary fragments corresponding to one or two

vessels, a little lump of red pigment, a flattened and smoothened

plaque of schist, a bone projectile point manufactured on a

camelid metapodium, as well as a bone tube. Tomb 2 is also a

chamber constructed over the surface but in this case an entrance

was registered (Figure 4). In this secondary burial the remains

of seven individuals were recovered. They were accompanied by

almost 100 necklace beads made of bone, carbonate rocks, black

lutite and turquoise, fragments of a tweezers and a pendant of tin

copper, two lumps of blue pigment composed by ground azurite,

atacamite green powder and oropiment yellow, as well as two

skulls of Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata s.p.). Recovered pottery

includes fragments of nearly 14 local and non-local ceramic

vessels and a small Humahuaca Black-on-Red style dish, probably

used for the offerings of solid or semi-solid aliments.

The grave goods found in Tomb 2 are significant due to the

symbolic value of the ornaments, colored powders and duck

skulls. The scarce presence of pottery and its fragmentation degree

allow us to suggest that these could have been the remains of the

vessels offered in the primary burial that with the subsequent

manipulation of the remains, probably in one or more rituals,

could have fractured and being replaced by other elements. Tomb

3 corresponds to a semi-circular chamber constructed above the

occupational floor (Figure 4), in which the secondary burial of a

woman of approximately 40 years old was found. The grave goods

consisted of a black polished dish, some camelid bones, fragments

of about six ceramic vessels corresponding to different local and

foreign styles, as well as two metal topus (pin decorated at one

end, used for holding clothes), one of them manufactured with a

silver and copper alloy that would not be local. Scattered among

the bones orange realgar powder was also found.

The elements integrating this woman’s burial would reflect

gender and social or ethnic identity distinctions. The topus were

symbols clearly related with the feminine in Inca times and until

the Early Colonial Period, serving as gender indicators. The fact

that at least one of them was non-locally manufactured and the

presence of Yavi-Chicha and Casabindo vessels from the highlands

allow us to think that the buried woman was native of the Western

Jujuy’s Puna or that she had strong bonds with that area. Tomb

4 was the only primary burial found, located in the interior of a

large vessel that was interred in the floor of the external space

to the tombs (Figure 4e). Inside the vessel, the remains of a 7

years old boy and a perinatal of 38-40 gestation weeks were

found. The grave goods that accompanied the infants included

two chisels and fragments of a tweezer, all manufactured in tin

bronze; two pink polished aribalos and two Humahuaca-Inca

bowls. The elements composing the grave goods of Tomb 4 would

be expressing the idea of Andean duality, manifested in several

organizational aspects of this society [42-44]. In this case, there

are two children of different ages, buried alongside two bowls,

two aribalos and two chisels. The fact that these elements were

also of different sizes -one larger and one smaller-, allow us to

suggest a correlation between the age of the children and the

size of the objects conforming the grave goods. Thus, a network

of meanings between the children, the bowls, the aribalos and

the chisels could be established. These would be expressing the

dual world-view of the groups to which these children belonged,

as social practices that could manifest in different circumstances

and diverse materialities.

Three of the tombs were found in structures built above the

occupational floor. This situation expresses a change in contrast

with the previous local funerary pattern, which consisted in

tombs located under the floor of domestic units. Besides, these

three tombs consist on secondary burials -that in two cases

are ossuaries- containing the remains of several individuals of

different ages. This situation would evidence the manipulation of

human remains in periodic re-opening of the tombs. Therefore,

we argue that a space for the veneration of the ancestors may

have emerged in Esquina de Huajra, constituted by an area of

congregation of few individuals directly in charge of mortuary

rites and by stone chambers that would have had a high visual

impact not only in the settlement but also in the surrounding

areas.

Pucara de Tilcara

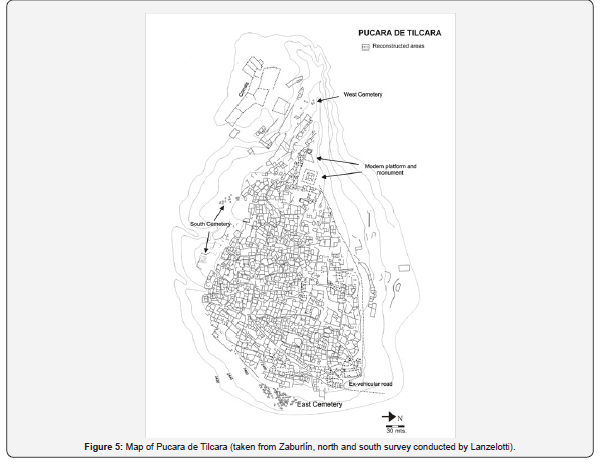

This archaeological site, located in the central sector of

Quebrada de Humahuaca (Figure 5), is known for being the

largest pre-Hispanic settlement in the region. The beginning of

its occupation corresponds to the 12th century, but it is during

Inca times when the settlement’s size increased as a consequence

of an accelerated rise in population density. As a result, several

structures were remodeled and terraces were expanded to build

new houses and workshops [20]. The approximately 580 detected

structures allow estimating that the site could have housed

more than 2.500 inhabitants dedicated to diverse productive

activities and in some particular cases administrative tasks. The

architectonic features of some buildings and the importance of the

objects found in them led us to believe that an important number

of religious leaders linked to the Empire may have lived in Pucara

de Tilcara (Figure 5).

The settlement apparently functioned as the capital of the

Inca province or wamani of Humahuaca. Besides fulfilling political

functions, as its mentioned by González & Williams [46], this was

an important productive center. The recent excavations carried out

in eight sectors of this site and the review of materials recovered

during the early 20th century that are currently preserved in

three Argentinian museums, allowed to detect over 50 metallurgic

and stone workshops. These workshops can be defined as houseworkshops,

since evidences pointing out towards both domestic

activities and multi-artisanal production [47] destined to the

specialized manufacture of metal and stone goods.

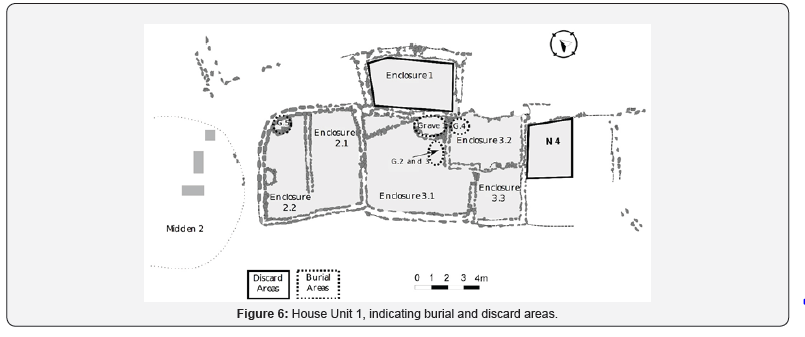

Tombs in Housing Unit 1

Housing Unit 1 (Figure 6) is one of the house-workshops that

provided the most information about the artisanal labors, since it

was intervened with modern excavation techniques, uncovering

almost its total surface [48,49]. This unit represents a house

located in two terraces of the inferior extreme in the Pucara’s

southwestern foothill, known as “Sector Corrales”. The excavation

of four of its enclosures and two patios, covering 127m2, revealed

a continuity in its occupation, between the 13th century and the

late 15th century or maybe beginnings of the 16th century AD

[50]. This house-workshop, destined to metal objects production

during the Inca domination, was abandoned as a productive and

housing space in order to be used as a graveyard. Five burials

were detected within the central and lateral patio [20] (Figure

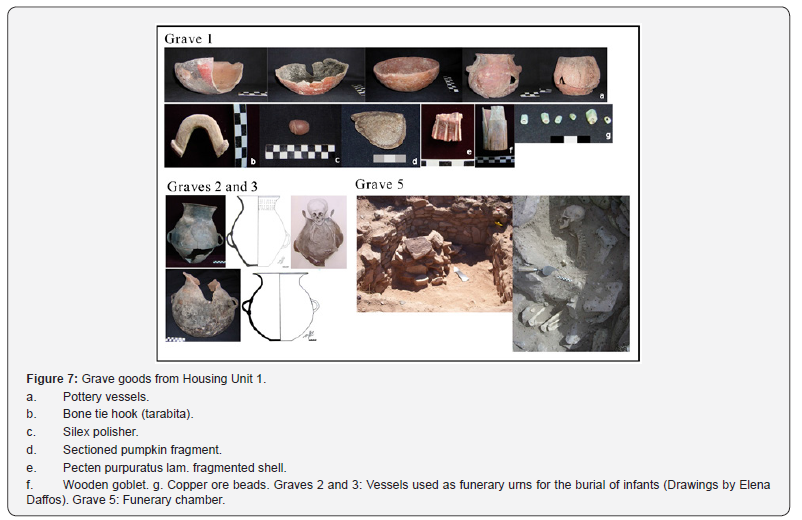

6). Built above the occupational floor of the central patio, Grave

1 (G1) constitutes an ossuary (Figure 7). A curved wall attached

to the perimeter of this patio was used for its construction. The

dimensions of this chamber (1,6 meters wide x 1 meter long)

indicate that it was built with the purpose of burying several

individuals, of which 11 adults and 10 immatures were identified

[51] (Figure 7).

It was possible to distinguish a first burial event,

corresponding

to an infant, whose remains were articulated and covered with

a thin ash layer [52], and was accompanied by a copper and

aragonite beads, as well as by materials that are not frequently

found due to conservation issues, as a wooden beaker conserving

pigments and fragments of wood and calabashes recipients with

red paint impregnations and a siliceous polisher. Subsequently,

the second phase took place as a secondary burial where several

human bones were placed, massively and intermingled. Theses

bones were also covered by numerous and successive ash and

charcoal lenses, which served as ritual marks for distinguishing

each burial event. Among these human remains fragments of

ceramic pitchers and bowls, a fragment of spatula or loom stick,

camelid bones, pieces of wood -some of them shaped as shafts

with remains of red painting-, remains of molds for the production

of metal objects using the lost wax technique, over 40 calabash

fragments -probably used as liquid containers-, pigment’s lumps

of several colors and a bone tarabita (a tie hook) used for tying a

funerary bundle were detected as mortuary offerings. The ceramic

pieces deposited as grave goods show evidence of a previous use.

This situation also appears among restricted vessels used as urns for

the burial of two infants along the eastern wall in Enclosure

3.1, denominated Graves 2 and 3 (G2 and G3). They were located

alongside the eastern wall of the patio and lineally to G1, and they

may have been contemporaneous to the first moment of use of the

chamber (Figure 7). Grave 2 corresponds to the burial of a 3 years

old infant with a tabular cranial deformation [52], placed inside

an “Angosto Chico Inciso” pot that was longitudinally fractured.

This pot presents abundant soot in the surface, especially in the

lower body and base, demonstrating its previous use for cooking

foods expose to long terms fire as arrope.

The burial identified as Grave 3 corresponds to an infant of

approximately 3 months old placed inside a large ordinary pot with

evidences of fire exposure. This pot was placed vertically without

its base, which was probably sectioned for introducing the infant,

since the opening of the vessel does not exceed 15 cm in diameter.

The opening was sealed with a mud layer and the base of a pitcher

was placed above it as a cover, in such a way that its internal

surface was exposed. Inside this base, large amounts of soot were

registered, suggesting that it was used for burning offerings.

Grave 4 was identified in the Northwestern corner of Room 2 in

Enclosure 3. It also corresponds to the burial of an infant that was

placed over the floor of the room. In this case, several bones of the

skeleton were missing, possibly as a consequence of a subsequent

extraction or maybe due to the context’s perturbation caused by

the falling of the supporting wall located in the upper step. Part of

these remains was found covered by a layer of consolidated mud

and surrounded by ashes. Three ceramic pieces were identified as

grave goods. A Fifth grave (G5) was located in the Northwestern

grid in Enclosure 2.2 (Figure 7). In the Northwestern corner of

this patio, about 10 cm below the surface, the skull of an adult

was found. After cleaning this context, it was confirmed that the

skeleton was complete. This is the reason why we argue that it

was a primary burial, in which the body was deposited in fetal

position inside a 1 x 1meter stone chamber, partially fallen at

the moment of excavation. The collapse of this structure must

have occurred when the remains of this individual, identified as

an adult woman, still conserved its soft tissues. The skeleton is

articulated, so it must have fallen over its left side and its lower

limbs remained underneath the rocks forming the eastern lateral

wall of the chamber. The occupational floor was cleaned in order

to build this mortuary structure, such as Grave 1.

The falling of this structure must also have affected

the

disposition of materials found associated to this woman, some

of which must have been included as grave goods [53]. On one

side, along the skull a red pigment lump was found and beneath

the pelvis a projectile point with notched base. Once the set of

stones conforming the burial was removed a small lens of ashes,

dispersed carbons, burned camelid bones and a shallow hole

were detected. These evidences could indicate the placement

of offerings and the preparation of the floor for the burial by

means of burning and smoking (sahumado) the context. From

this hole, we extracted wood remains, among which we identified

fragments of a spoon handle, and a tube manufactured on a bird bone.

Several bone alterations were identified in the bodies of the

buried adults, accounting for pathologies of postural origin and

periodic stress probably associated to artisanal activities carried

out in this Housing Unit.

Other aspect demonstrating the link between the deceased and

the development of artisanal activities in Unit 1, and that in turn

highlights the filiation with the individuals that occupied it, is the

kind of offerings included as grave goods and the ritual practices

that honored them, even in moments well after their burial.

Regarding the type of grave goods found, it is worth mentioning

once again the finding of a beaker with pigment remains inside,

pigment lumps, wood remains with red paint impregnations and

the siliceous polisher found at the base of Grave 1, all of them

making clear references to ceramic production. These findings are

complemented by the identification of a Humahuaca Black-on-

Red small pitcher, which appeared outside this chamber, buried

in proximity to the foundations of the structure. Inside this small

pitcher with sectioned neck, three siliceous polishers were found,

likely deposited as an offering.

The only indicators of metallurgic activity detected are the

remains of molds and the powder with content of copper, which

were included as grave goods. The numeric difference between

these materials and those linked to ceramic production could

indicate that the primary activity of this housing unit was pottery.

Thus, the assemblage of grave goods could be considered as

sensible signs or informational material components about

the personality of each buried individual. From the moment in

which polishers and pigments, among other materials, were

included in these funerary contexts, they lost their “neutrality”

and transformed into attributes corresponding to particular

individuals [54]. Different kind of objects, from those previously

used in artisanal activities to ceramic pieces used daily for

the processing and service of food, were re-signified by their

introduction in a sacralized and ritualized context. Despite the fact

that in some cases they continued playing their roles, as sharing,

serving and containing aliments, they must have acquired a new

symbolic value by being used for a different type of consumers:

the deaths. This new form of consumption must not have been

a destructive act, considering that death was not imagined as a

definitive end.

The bond between the living and the deaths that occupied Unit

1 must have also symbolically endured through time, renovated by

conducting commemorative events after the house abandonment.

The finding of a small pitcher that, considering the dispersion of

its fragments, should have been placed on top of the ossuary and

fell down when it collapsed, is an evidence supporting this idea.

According to its decoration, this vessel can be attributed to the

Hispanic-Indigenous Period (ca. 1536-1595 AD).

Pucara de Tilcara’s cemeteries

The presence of ancestors in the daily life of the Pucara’s

settlers can also be perceived in the segregation of collective

burial areas. This is a distinctive feature of the site, only shared

with another important settlement occupied during late pre-

Hispanic times in Quebrada de Humahuaca: Pucara de Volcán. In

the case of Pucara de Tilcara, these areas (Figure 5), described as

East, West and South cemeteries are found next to the main access

roads to the site and to some housing sectors. The location of

these cemeteries evidence that a numerous set of structures, daily

occupied for the development of artisanal and ritual activities

were spatially framed by the presence of the deaths. Beyond their

inclusion within domestic spaces, the existence of these collective

burial areas indicates an intention of signaling the perimeter of

the Pucara with the ancestors.

Pucara de Tilcara is one of those sites that cannot be defined

as pucaras in a strict sense, which is to say in the way of a fortress

[55]. Although this site presents some features that could be

defined as defensive, such as its location over an elevated geoform

that provided a broad view of the surroundings, this could also

respond to a supernatural reason, considering that the hills were

identified as the dwelling site of the ancestors [56]. In this sense,

the construction of over 130 graves in different foothills of this

site and alongside the main access roads, in some cases occupied

by 18 individuals or more [57], perhaps could be manifesting the

use of landscape traits linked to the necessity of projecting a sense

of pertinence and collective memory [58]. In turn, delimiting the

settlement perimeter through the presence of the deceased could

express that the cult to the ancestors was, among other aspects,

linked to the search for protection of its inhabitants.

Discussion

In spite the variety of funerary practices from Inca moments

registered both in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara, it is

possible to point out some common elements that would allow us

to characterize mortuary practices during Inca times in Quebrada

de Humahuaca. Among them, we must highlight the presence of

graves with positive traits that in some cases constituted true

burial chambers that could be considered as “monuments to

the ancestors” (as Grave 1 in Housing Unit 1 from the Pucara de

Tilcara and Graves 2 and 3 from Esquina de Huajra). Although

the characteristic pre-Inca funerary pattern of Quebrada de

Humahuaca points to graves located below the occupational floor

of the houses [59], there are some cases where raised tombs

similar to the ones mentioned before were found, such is the

case of Complex A of Los Amarillos site. This situation would be

directly linked with the communal cult to the ancestors [35].

By adding the presence of ossuaries in both sites (Grave 1

from Tilcara and Graves 1 and 2 from Huajra), the evidences of

periodic extraction of the remains or possible re-burials, and the

geographic closeness of burials to settlement spaces, it is possible

to argue that burials in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara

refer to a marked tradition linked to the cult to the ancestors

and that this can surely be traced back to pre-Inca times. As it

has been defined for other Andean cases, these manifestations

related to the veneration of the deceased could have been seeking

the regeneration of crops and productive cycles in general, at the same time that ancestors could benefit the community since

they possessed part of the fertility’s control (Arnold and Hastorf

2008). Therefore, the analyzed graves would allow a continued

access to the remains of those people considered important

(Gluckman 1937, cited in Morris 1991), whether for the social

group as in the case of Huajra or for the reproduction of a family

group as in Housing Unit 1 in the Pucara de Tilcara. Independently

of the hierarchy of the deceased, given that we know that not

every predecessor was considered an ancestor (Kaulicke 2001),

we observed a frequent manipulation of the remains for the

separation of skeletal parts, their re-location and even their

shaping, in contexts both domestic as supra-familiar.

In the case of Esquina de Huajra, we consider that Terrace

3 would have established as a public space where several rites

linked to the cult to the ancestors could have occurred. This high

visibility space would have functioned as a scenario where a group

of people congregated in the reduced space external to the graves

(approximately 50 m2) could have conducted the corresponding

rituals, being observed by the other settlers. The fact that Grave

1 and 2 were constructed over the occupational floor points to

their visual impact from different sectors, especially from the

North. On the other hand, the absence of covered graves would

allow a continuous access to the remains of the deaths, reinforcing

the character of these burials as “monuments to the ancestors”

who were regularly called upon to “give food and drink to the

deceased” [35].

Meanwhile, in Pucara de Tilcara we are faced with the redeposit

of remains that possibly involved the development of

ritual practices at an intra-domestic level. Nevertheless, given that

the burial chamber was located in the large central patio, these

practices should have been visualized from several points in the

foothills. Perhaps, these celebrations came to exceed the limits

imposed by the domestic and private plane, therefore remarking

with each commemoration a kinship line and the coexistence

of the deceased with the other settlers of the site. Regarding

the cemeteries of Pucara de Tilcara, segregated areas from the

housing units used specifically for the burial of the deceased, it is

relevant their presence in the limits of the settlement and linked

to the main access roads. In this sense, cemeteries could have

reinforced the protection of the ancestors over Pucara de Tilcara’s

inhabitants, being constantly visualized. This spatial configuration,

embedded by the symbolic and the ritual, highlighted the multiple

composition of the functional character of this settlement as an

administrative, politic and religious center. In Esquina de Huajra,

we have not found cemeteries of this type, allowing us to think

that perhaps their presence in Pucara de Tilcara could be related

with its functionality as capital of the province during Inca times.

On the other hand, the presence of cemeteries may indicate the

need to place the bodies of the deceased in segregated areas,

due to the fact that many housing spaces would continue to be

used. Considering the population density that Pucara de Tilcara

had during the Inca Period, concentrating a large population

destined to artisanal production, it is possible to estimate that

the settlement would require to occupy every house and patio on

artisanal tasks.

Another common trait to both settlements is the presence

of direct burials exclusively dedicated to adult women (Grave 5

from Pucara de Tilcara and Grave 3 from Esquina de Huajra). The

inhumation of these women, elderly for their time (over 30 years

old approximately), could indicate the role they played within

Inca social structure. In the case of the woman found in Pucara de

Tilcara, her individualization from the whole of society could refer

to the ritualization of her tasks and artisanal activities with the

intention of exalting those values associated with the fulfillment of

the chores [60]. Likewise, probably in both burials people sought

to highlight their power as life generators, following certain

principles of the Andean mythology in which the role of women

and feminine deities, linked to the procurement of sustenance

necessary for human reproduction, is raised [61]. The associated

grave goods of both women tend to highlight their identity

features. In the case of Tilcara, her figure as artisan is manifested,

while in Huajra the objects refer more to her provenance, probably

from the Puna.

These distinctive features were also registered in the other

burials. In Esquina de Huajra, the elements included as offering

specifically refer to links to other environments, as the highlands,

while in Tilcara they seemed to reflect the kind of artisanal

activities developed. As we mentioned before, these differences

possibly responded to the sites’ functionality. Nevertheless, it is

interesting to highlight that this is only expressed in the grave

goods corresponding to sub-adults and adults’ individuals.

The burial of children and infants in urns are frequent in both

settlements. In these cases, we observe the re-utilization of

ceramic pieces whose primary function was food processing, an

action demonstrating that these pieces were not manufactured

specifically for the inhumation of short aged children. The absence

of objects destined to function as mortuary offerings for these

children in the case of Pucara de Tilcara could point out that they

were not considered subjects with a constituted social figure as in

the case of young and adults. Their placement inside urns buried

below the surface level of residential floors perhaps add to this

condition, given that in a certain way they remained invisibilized,

in opposition to the apparent exposition of those individuals

placed in positive traits.

These multiple ways of treating the deceased and, above

all, the periodic contact with their remains, demonstrate that

in Quebrada de Humahuaca, as in other Andean regions under

Inca domination, the cult to the ancestors kept playing an

important role for the reinforcement of local identities, in certain

contexts with clear hints of “Incaization”. This refers, in a case,

to intentionally demonstrating the active role of artisans within

the state structure, and in the other, to express the provenance

of certain individuals, maybe as a reflex of the displacements of

dominated populations. On the other hand, the meaning given

to death is exposed once again. Contrary to an occidental point

of view, where death is presented in opposition to life, mortuary practices registered here manifest the way in which the power

of past generations conditioned daily life. In this sense, the

deceased were presented as materially close and participants

of daily decisions. This coexistence and continuity in the cult to

the ancestors was possibly the one that laid the foundations for a

resistance of regional identities, extremely accentuated before the

Spaniard’s arrival. The mortuary contexts in Huajra and Pucara

de Tilcara could be a sample of this resistance, with datings

ascribable to the Hispanic-Indigenous Period [62,63]. Practices

destined to maintaining this cult probably revealed that “what

was to be done, was done” with the hope of ensuring prosperity

and fertility. During the decline of the Empire and even more in a

region distant from the capital, local societies had to reformulate

their idiosyncrasy, putting into play the collective memory and

slowing down the incaization process.

Acknowledgement

To the technical staff and researchers of the Instituto

Interdisciplinario Tilcara, Lic. Pablo Ochoa, Daniel Aramayo,

Armando Mendoza, and Presentación Aramayo, who collaborated

with the digging tasks on Pucara de Tilcara. To Myriam Tarragó,

María Asunción Bordach and Osvaldo Mendoça for the information

provided on their research in Housing Unit 1. Also to the Tumbaya

Aboriginal Community for their support to the research. The

research was founded by the following projects: PICT 2015-2164,

PICT 0538, CONICET- PIP 0060, PAITI Res (D) 2271.

To know more about Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment