The Fabric of Canada- Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Of Making Cloth with Sheeps Wool Smallest and smoothest pile grow on the pole. The coarsest about the Tayle. The shortest on ye head and on some parts of ye belly. The longest on ye flanks. Being sorted to wash it in ordinary water, in soape, then its dyed in rase otherwise it is wrought while into cloth and the cloth dyed afterwards [1].

The textile industry changed in the 17th century from

one which depended on the domestic “cottage industry” for supplies to

one which became reliant on mass-production and a cosmopolitan trade

network in which North America became a consumer [2]. The rise of the

warehouseman and the factory meant that the small markets and halls used

when goods were produced in homes by families were abandoned for inns

and warehouses [3]. The introduction of the New Draperies, which were

manufactured with different looms, used worsted yarns, which produced

finer fabric, with a higher thread count [4]. The quotation above

reflects upon the domestic clothing industry of the 1660s in England,

which, with the introduction of the New Draperies and ready-mades, would

by the 18th century be forever changed [5]. Clothing would become more

disposable as cheaper methods for weaving, knitting, dyeing and

constructing would become available. Because a society’s costume helps

to define groups by country, region and status, changes in its

production impacted society in other ways. As a consumable, this

commodity, in terms of wool production, was England’s major export from

the Medieval period through to early modern period [6]. This commodity

afforded England the financial capability to explore other geographic

regions and allowed it to become one of the largest Empires of the

Modern Period. The fabric of a nation, however, is not based solely on

its economic wealth. Once the fibre is woven into cloth, dyed, and

constructed into a garment, it becomes an item which can define a region

and status. Personal items such as costume are adapted to fit

the needs of smaller groups, such as colonizing peoples, within a

nation.

The textile industry and costume construction and

style influenced 17th -century society, from being a major industry to

contributing to the stratification of social structure and the notion

that the “clothes make the man”. We can therefore garner information

about the past by examining archaeological textile remains, extant

textiles, and textile images portrayed in printed images.

Many questions arise from the research previously

described. The examination of the Ferryland textile collection has aided

understanding of English colonial life in the 17th century. This has

been made possible by employing a variety of techniques including the

archaeological and analytical sciences, the results of which have been

described in previous chapters. The following discussion will combine

information gleaned from this analysis. The importance of the small

finds excavated from an undisturbed 17th -century privy has shed light

on the many changes that occurred in this period on the north eastern

American continent.

The Ferryland Collection

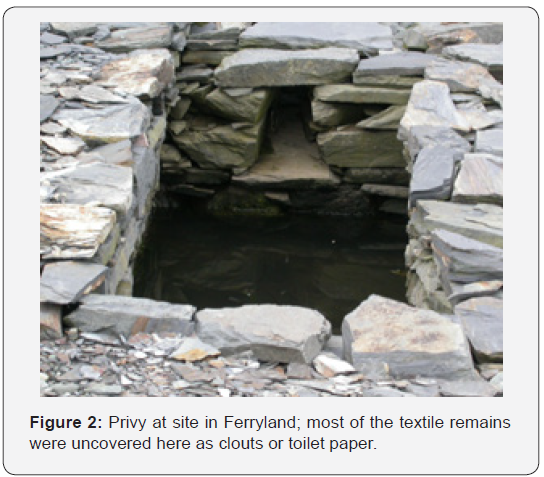

The bulk of the textile remains that comprise the

Ferryland textile assemblage were excavated from a privy, in use from

the 1621, to the early 1670s, when it was capped following the Dutch

raid in 1673. Hundreds of square fragments of cloth excavated from the

privy, were used for hygiene purposes, but by whom? The scraps of silk

trim were likely scraps from a tailor, possibly William Sharpus or a

second tailor who replaced him, but from which household? Captain Wynne

arrived in Ferryland in 1621 with a dozen settlers [7]. Twenty more

settlers arrived in 1622 including a tailor, a surgeon, blacksmiths,

fishermen,

boat masters, a husbandman, a quarryman, women, children and

servants [8].

At this point there is mention of a kitchen, a parlour, a

henhouse, defensive works, two tenements, salt works and

a forge having been built, and with a brew house under

construction [9]. Calvert visited the colony in 1627 and in 1628

he brought his family and an additional 40 settlers to Ferryland.

The following year he quit the colony, moved his family back to

England and went south to explore the Chesapeake area [10].

The Kirke’s arrived in Ferryland in 1638 bringing some 100

settlers. They continued to build (for example the Kirke houses

at Area F), and profit from the rich fishery [11]. Captain Wynne,

who directed the initial building phase including the warehouse,

seawall and privy of Area C, made his buildings to last, which is

in part why they exist today. Although not directly referenced to

in any of Wynne’s letters, one of his letters dated 1621, alludes to

the construction of the “Harbour” [12]. This reference indicates

that the privy, which was part of the seawall construction, may

have been available for use as early as 1621. Wynne may well

have been one of the first to use the privy. As Governor of this

colony (and an employee of the East India Company) he could

likely have afforded the luxury of clouts for the privy.

To date, the Mansion House, Calvert’s residence, has not

been found. No privy is mentioned in Wynne’s descriptions of

the Mansion House. We think, therefore, that Calvert also likely

made use of the privy. Chamber pots, though available at the

time, have not been found in any quantity among the ceramic

remains at Ferryland. It is therefore possible that all of the

gentry used the waterfront privy. Given its public location, it is

possible that was used by gentry-class men who did business

with incoming and outgoing ships. It may also have been used by

gentle women, such as Lady Kirke, who, with the help of her sons,

ran her husband’s business from 1651 until her death sometime

in the 1670s [13]. One thing that is certain is that this privy was

associated with a work area, rather than a domestic structure.

The privy was therefore likely used by all involved in the fishery

from those who fished, to those who sold the final product. In

terms of the textile remains left in the privy, the difference may

have been between those of a gentry sort had clouts to use and

the fishermen who did not. This could explain the high-quality

wool fragments used for hygiene purposes. The tailor’s scraps of

silk cloth and trim, unsuited to hygiene purposes, may have been

deposited in the privy as a deterrent to reuse by those of a lower

standing. It is almost certain that a tailor resided or worked near

the privy, or that his place of work drained into the privy.

The Ferryland Archaeology Site

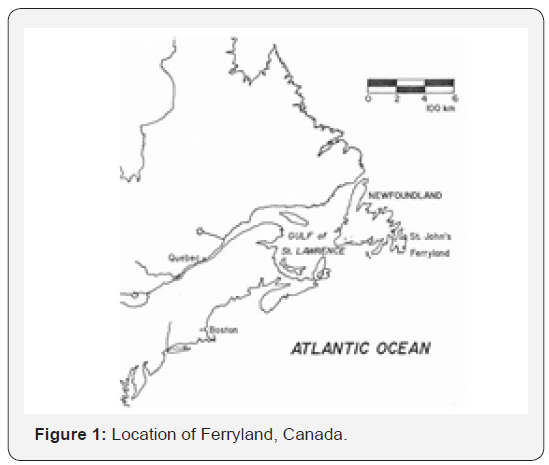

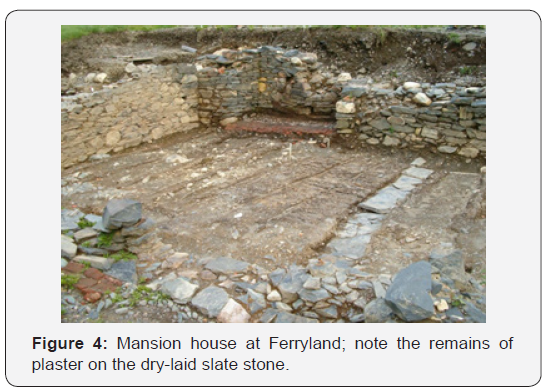

Excavations and analysis have been completed for Areas

A, B, C, and D (Figures 1-4). The excavations of Areas F, and G

are on-going, and analysis is still being conducted. Of interest

here are the domestic structures, as they would have the highest

potential for costume-related artifacts. Nixon and Crompton

reported on houses of the middling sort in Areas B and D,

respectively [14]. Neither household held numerous costume

remains. This is in part because of burial environments unsuited

to the preservation of textiles. Therefore, metal costume-related

artifacts comprise the assemblages. In Area D, however, one

textile fragment was found, CgAf-2:78983, three button holes

with silver metal threads. These appear to have been from a coat

of the late 17th century. They had been cut out of a garment and

represent the potential reuse of the metal threads. Other items

include cuff-links, CgAf-2:80876, from Area D and a shoe buckle

from Area B, CgAf-2:145219 Event 145. The Area B buckle is a

rectangular shape with a drilled frame for a separate spindle

and dates from 1690-1720 [15]. The costume remains from

Area F are also dominated by metal artifacts because of its burial

environment and far outnumber those of Areas B and D. This

agrees with ceramic data which clearly shows the Area F house,

or Kirke house, to be of a much higher status than those of Areas

B or D [16].

Excavations at Ferryland have yet to locate the colony’s

cemetery. During the almost 80 years of occupation during the

17th century, people at Ferryland would have died. It is likely

that Lady Kirke is buried near the colony at Ferryland [17].

Though the burial environment of the cemetery may not be

sympathetic to organic preservation, it is possible that a woman

of Lady Kirke’s status would be buried in a lead coffin, like those

of status found at St. Mary’s City buried in lead coffins, which

could afford better preservation [18]. Without this additional

comparative information our interpretation of the site cannot

help but be biased by what has been found to date. One must

therefore carefully define the features with which we interpret

the costume components of the Ferryland site. The bulk of the

textiles are from the waterfront privy. Other related materials

come from two middle-status houses, and one gentry house.

Seventeenth Century Textiles

The following cloth descriptions are based on those used by

Kerridge [19]. The cloths are presented in roughly chronological

order beginning in the 14th century and ending in the 17th

century. The earlier cloths continued to be used during in the

17th century and therefore are included. These include: says;

kersey cloth; Suffolk cloths; worsted says; worsted satins;

camlets; russells; silk damasks; jerseys; mixed stuffs; worsted

stuffs; baize; flannels; serges; linens and broad silks [20].

Says were tabby-woven while kersey, of a thicker yarn, were

twill woven and used for stockings [21]. Serges, produced in

Southampton, were also a woven with a thick yarn and fulled

to give extra warmth. Serges replaced the kersey wool but were

used for more than stockings [22]. Suffolk cloth was dyed blue

[23]. Cloth made with longer wool fibres called worsted, such

as worsted says or russells, gave a similar shiny appearance to

silk but were much cheaper [24]. Russells were therefore used

to make gowns, coats and petticoats [25]. Double russells,

manufactured in Norwich, were used to make petticoats, spring

and summer coats, scholar’s gowns, men’s vests, waistcoats and

women’s boot and shoe uppers [26]. Camlets, also produced in

Norwich using a highly twisted yarn, were used to make bodices,

breeches, drawers, cloaks, gowns, jackets and petticoats. The

russells and camlets were a finer cloth [27].

A baize was a mixture of worsted warps and carded weft

threads made of shorter hairs than worsted. Baize would have

been fulled and was popular to the 1620s. Flannels were similar

to the baize with a worsted warp and carded weft. Flannels were

used for undervests, underpants, drawers, trousers and shirts

[28]. The process of fulling wool cloth required access to water.

Exeter, which was beside a large river, had a large fulling mill

[29]. Based on descriptions of cloth by Kerridge, it is estimated

that most of the 183 tabby-woven wool samples represent

russells, camlets, says, serges and flannels. The few samples of

2/2 twill wool could be classified as kersey wools. Many of the

kersey wools were used for cloth stockings; when knit stockings

became more popular kersey wools fell out of favour [30].

Discussion

The archaeological record does not preserve all

materials

left behind by people. It would therefore be unfair to make

a judgement on the export English cloth industry of the 17th

century based on privy and midden remains from Ferryland.

An undisturbed site, such as the Ferryland privy, can provide

support for the availability of materials identified in archival

documents. The organic components of material culture are

generally less well represented in the archaeological record.

The most durable of artifacts are those made from inorganic

materials. Those artifacts represent house-building materials,

such as metal hardware and stone foundations, ceramicwares

and glass items related to food preparation and consumption as

well as metal tools. Archaeologists use these better-preserved

fragments to identify the use of space within structures, types

of food preparation, possible foodstuffs consumed, the layout

of villages, workspace usage, status and wealth. Textiles rarely

survive burial. Sometimes associated costume components will

survive, such as bale seals from bolts of cloth, pins, buckles and

buttons. This record tends to be less biased by differences in

social class than those of the written, print, or image record.

For example, when the Ferryland site was attacked by the Dutch

in 1673, the resulting destruction and burial of structures and

artifacts affected occupants regardless of their social standing. The

destructive nature of the burial environment, however, acts

differently for each material type resulting in an incomplete

archaeological record.

A thorough examination of costume from the 17th century is

fraught with problems, the greatest being the fragile nature of

the materials from which clothing items were made. The wools,

silks and linens used in the construction of breeches, gowns and

shirts rarely survive the test of time. Researchers have examined

a variety of North American archaeological sites with textiles

remains and have found that, in general, only proteinaceous

materials survive, with some instances of cellulosics preserved in

the corrosion layers of associated metals [31]. Even when found,

not all fibres can be positively identified because morphological

characteristic may not be preserved [32]. Associated materials

such as metal buttons and buckles also fall victim to the

deteriorating affects of the burial and ambient environments.

Desiccating or waterlogged anaerobic environments lead to

long-term survival of textile fibres those made of silk and wool

[33]. Unfortunately, these burial conditions are rare. The soil

conditions of the privy at Ferryland consisted of a wet, thick

soil rich in faecal matter which afforded the preservation of

both wool and silk. However, even with this wet environment

not all components of a textile necessarily survived. Dyestuffs

were likely lost to leaching. Historically, natural dyes, generally

being fugitive, were used along with a mordant. During the

17th century the common mordants were aluminum, iron, tin

or copper. Mordants would complex with the dye and fibre to

produce a more permanent dye [34]. Although mordant dyes

have a better chance of surviving, they can be masked by staining

from the organic matter in the soil [35]. It has also been noted,

but not yet published, that weld dyes can act as antioxidants and

will help preserve organic textiles [36].

The Ferryland collection contains 237 woven wool samples

and approximately 18 cloth fragments made with silk fibres. The

textile collection from Ferryland has few silk pieces. If privies

were built for use by the gentry who were the most likely to

be wearing silk, why then does the Ferryland privy contain so

few silk fabrics? Based on the good condition of most of the silk

fibres examined, with wear being attributed to use (Figures 1-5),

it seems unlikely that the burial environment would preserve

some, but not all. This must be a function not of preservation, but

rather use, preference for wool by gentry, or availability. This may

also be related to differences in climate between Newfoundland

and Europe. The cooler temperatures of Newfoundland may have

led to many wearing warmer woollen clothes, rather than silk or

linen. One possible explanation may be that the Ferryland gentry

did not use this privy exclusively or to any great degree. Perhaps

the co-operative nature of proprietorship, under Calvert, dictated

that anyone was welcome to use the privy. Though the people at

Ferryland could have added to the cesspit during its last years

of operation, there is a consistently low concentration of silk

in these strata. Supply and access to markets also might have

something to do with the scarcity of silk. Wool manufactured in

England would have been more readily available [37].

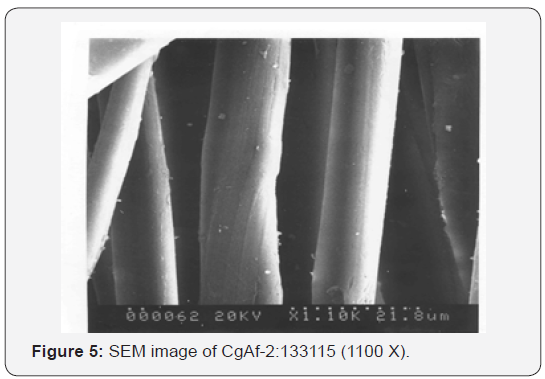

Fibre condition can tell us something about the use-wear of

the privy fragments. For example, about 40% of the silk fibres

examined exhibited cracks perpendicular to the length of the

fibre. This type of deterioration is indicative of a fibre that was

extensively bent during use indicating that it was worn a great

deal [38]. This may indicate that the other 60% of the collection

was not used extensively before being made into clouts. Some

of these samples include silk trim which was not likely used for

hygiene purposes, but nevertheless suffered little damage during

use. Some of the people of 17th -century Ferryland, with money,

did not appear to put much wear into their silk clothing prior

to discarding. Given that shipping to Ferryland was frequent,

the movement of goods such as individual costume orders was

possible and likely.

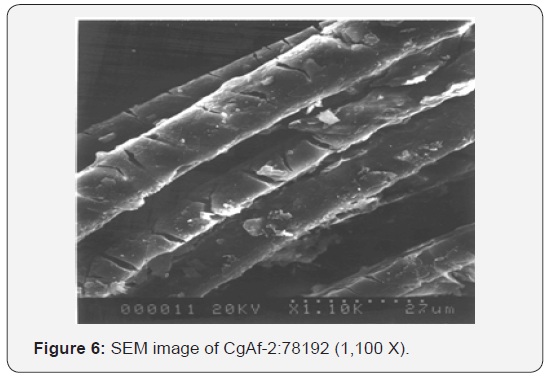

Other physical damage, such as microfractures along

the shaft of the fibre may be indicative of changes in relative

humidity in the burial environment [39]. Figure 6 shows such

an example. However, only about 10% of the assemblage exhibit

this type of physical damage. The well-sealed environment of the

privy made for a stable environment, based on its excellent state

of preservation.

One other consideration when examining condition is

the manufacturing techniques involved in textile production.

It appears that the New Draperies in the collection, when

examined under magnification, are in better condition than

the Old Draperies. This is probably a result of manufacturing

techniques. First, most of the New Draperies were dyed. If weld

were a popular dye at this time, its antioxidant properties might

aid in the preservation of silk and wool. Secondly, they represent

finer clothing and may not have been worn as often or for

laborious tasks.

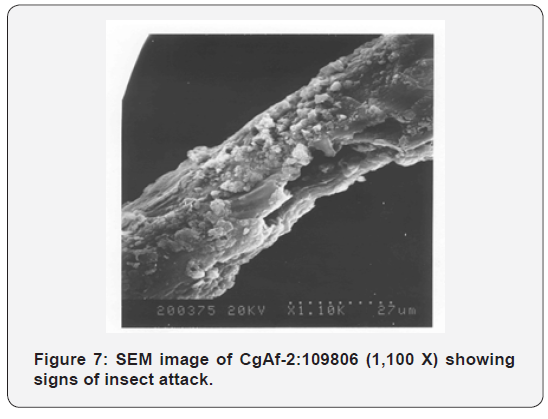

The environment of the privy, though stable in terms of

relative humidity, resulted in different preservation. Textiles

found in the upper layers show evidence of insect attack (Figure

7). Wool found in the lower levels is better preserved and silk

found in the upper levels is better preserved. Rootlets were

absent throughout the privy. The faecal content of the privy

matrix may have inhibited plant growth.

Fungus and bacteria were able to establish colonies once

the feature was opened. Both fungus and bacteria can abrade

and fracture fibres as they grow within the fibres. Some of this

type of damage can be seen on the fibres, but it is not great. One

explanation could be that the backfilling done to over-winter

the privy feature after its first year of excavation was successful

in creating an anoxic environment, lowering the survival rate

of bacteria species [40]. Archaeoentomological analysis of the

Ferryland privy indicated a population distribution of beetles as

follows: 33% in Event 116, 30% in Event 49, 30% in Event 50,

17% in Event 170 and 8% in Event 111 [41]. The percentage

differences of entomological remains could be either a factor

of population fluctuation, burial environment preservation, or

both.

In silk fibres the fibroin decay begins in the amorphous

sections. This type of degradation, of crystal structure, results

in a loss of orientation making the fibres weak and brittle. Metal

thread fragments are often preserved with the core textile, but

the substrate textile is missing because of the deteriorating

effects of burial. It is therefore difficult to predict to what object

the metal threads were attached. It is virtually impossible to

distinguish between metal threads used for costume and those

used for tapestry as they were produced alike and often in the

same shop [42].

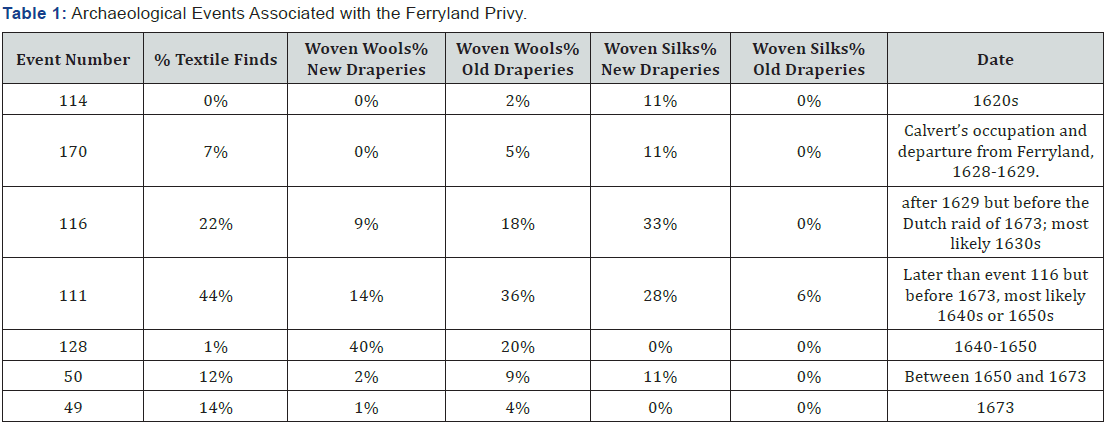

Based on the distribution of textiles (Table 1), Event 111

appears to have offered the best environment as 44% of the

collection was found here. This could also indicate a higher rate

of consumerism and disposal during this period. Entomological

remains were lowest for Event 111 which, if preservation was

very good, might be expected to be higher. This may also indicate

that consumption was high during this period and that insect

population within the colony was low. The highest percentage

of silk was found in Event 116, with Event 111 a close second.

Entomological remains were highest for Event 116, perhaps

indicating that they were consuming silk, with a preference to

this keratin over wool. Overall, however, Events 116 and 111

contained the highest quantity of both silk and wool, probably

accounted for by environmental preservation but also by the

size of the human population, the availability of goods and the

ability to purchase.

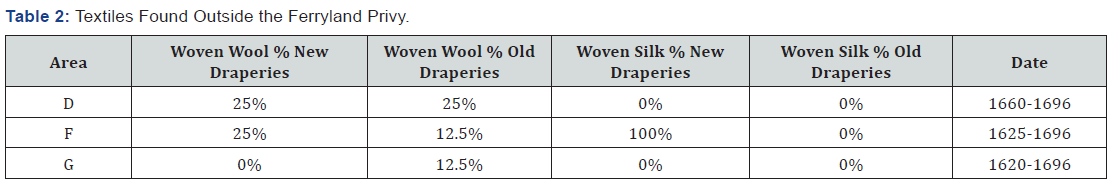

Table 2 presents the distribution of textiles found outside the

privy. Area F contains the only silk remains. This is not likely

related to preservation but is more likely a fact that this was

the result of the area of a high-status residence where silk

would have been affordable and worn. The woven wool New

Draperies were evenly distributed between Areas D and F. The

Old Draperies were concentrated in Area D which represents a

household of middling sorts.

Based on both the information reported by Kerridge,

regarding textiles from the 1600s, information garnered from

textile researchers abroad and the Ferryland archeological

textile collection, it appears that the following cloth came to

North America in the 17th century: serge; kersey; resells; camlets;

worsted says and satins; flannels; braize; and broad silk.

From the wool textile fragments found in the privy, we know

that men could have had clothing constructed from coarselywoven

cloth and finely woven twill and tabby cloth. The coarsely

woven tabby cloth likely represents a working type of breeches.

Breeches waistbands found were of a slightly finer weave, with

a 7/9 thread count, and possibly represent a pair of non-fishery

working or common breeches. There were doublets with long

tabs which were popular in the early 17th century. Fragments

which probably represent doublet wings or epaulettes were

also present and these match the doublet tabs (in terms of date)

that were also present. Fragments CgAf-2:97654a-c and CgAf-

2:106584 appear to be of a similar twill-woven fabric, possibly

from a doublet, and represent the New Draperies. The former

fragments are from a late 17th century context from the Area D

house, while the latter came from the lower levels of the privy.

These samples suggest that one bolt of cloth may have made its

way to Ferryland early in the century and was used throughout

the century. Or, more likely, this could indicate that similar types

of fabric were shipped to Ferryland throughout the century.

The silk lace and silver point, CgAf-2: 90255, are sufficiently

short to indicate that it was used for decorative purposes,

probably for a doublet [43]. These laces with points remained in

use as decoration around the waist of a doublet until about 1630

[44]. There were a few pieces of silk velvet and two fragments of

silk damask indicative of high status. Designating fragments as

components of male or female costume is difficult as either sex

could have worn these fabrics in the 17th century.

Though cellulose-based fibres were not preserved, evidence

such as a bale seal, CgAf-2:315014, representing Haarlem’s fine

linen, indicates that lengths of linen were shipped to Ferryland

presumably for the construction of undershirts for both men and

women and children. Holland linen, as it was called in England,

was widely distributed in the 17th century, based on seals found

in London, Northamptonshire, Wiltshire, Edinburgh, France,

the Netherlands, Sweden, and the Pentagoet site in Maine [45].

Examples like the British Museum seals have also been found at

St. Mary’s City dating to the mid-half of the 17th century; these

may more closely match the Ferryland seal [46]. Though the

Ferryland seal is like the British Museum example, the numbers

inscribed on the seals, which represent cloth length, are different.

The silk damask fragments appear to be French since they

matched similar samples of damask from France in the Victoria

and Albert collection and in the Royal Ontario Museum collection.

Most of the wool samples were probably manufactured in

England. Silk trim, ribbons and samples of passementerie were

possibly manufactured in London by Flemish textile workers

[47]. Metal thread production is recorded as having been carried

out in Nuremburg from the 14th century [48]. It is likely that

there were other, non-recorded, sites of metal thread production.

Was this rapid transfer of fashion to the Colonies a result

of goods being imported directly from England or were they

shipped between the North American colonies such as Boston?

Or was it because print images were imported bringing news of

change? Each likely contributed equally, given that the costume

remains seem to indicate that a relatively fashionable population

resided in 17th -century Ferryland.

The likely manufacturing centres used for the textiles

represented within the Ferryland collection include England,

Germany, France and the Netherlands. The fact that shoe

buckles show up at Ferryland within a 1660s context indicates

that costume fashion and news of its change was available

to at least some of the residents of this colony. We also know

from documents that shipments of ready-mades numbering in

the thousands were coming to Newfoundland; no doubt some

were delivered to Ferryland [49]. The ready-mades were likely

intended for the middling sorts or their servants. The silk damask

and the fancy snuff box may have been produced in Lyons,

France. The silk ribbons were likely produced in Germany or the

Netherlands. Some of the porcelain came from the Netherlands,

while most of the stoneware mugs, jugs and bottles came from

Germany [50]. We know from bale seal evidence that fabric

came to Ferryland from Exeter and London. The silk damask

samples found in the top layers of the privy, which represent the

last phase of its use in the 1670s, seem to best match a French

provenance. The tulip and leaf pattern are very similar to those

fragments of silk fabric with a French origin in the collections

of both the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Ontario

Museum. That such rich silks were disposed of in the privy and not reused indicates a certain amount of wealth within the

colony, at least by those living near the privy (perhaps by those of

the Kirke household). We see evidence for the purposeful reuse

of textiles in the middling household of Area D. The elaborate

designs used in textiles and on other material culture in the 17th

century, provide evidence for the movement of consumables

and people beginning in Medieval Europe and through the early

modern period. Both periods are often viewed by the current

culture as unsophisticated, uninspired, dark and without human

comforts [51].

The material culture, however, provides evidence to refute

this notion, as illustrated by the artifacts described here. The

remnants of early works of art, revealed through conservation

provide further support [52]. Seventeenth-century Europe

underwent a great period of discovery, expansion, and

movement in terms of trade. The discovery of the Americas and

passage to the East Indies via the Cape of Good Hope changed the

movement of goods and world trade forever. A routine exchange

of commodities developed in which the Newfoundland fishery

was a significant component [53]. Contact between Europe,

America and Asia through commerce exposed Europeans to

foreign cultures through their goods (motifs were exchanged

along with raw materials) and reshaped Europe’s perception of

itself and its place in the world [54].

Dyestuffs can also tell us something about trade at this

time because they were a valuable commodity and were

documented by their place of manufacture [55]. Known dyes

were identified on 24 of the 59-fibre sample. In 15 samples

compounds indicative of red dyes (carminic acid, alizarin and

purpurin) were identified. Carminic acid was identified in four

burgundy silk samples. It was the only dye detected in two of

the silk samples (CgAf-2:127294 which was a burgundy brown

silk brocade and CgAf-2:124936 which was a burgundy silk).

Two other silk samples contained alizarin and purpurin, as well

carminic acid (CgAf-2:101147 which was a burgundy silk thread

trim and CgAf-2:124974 - burgundy brown silk brocade).

Nine wool samples and one silk sample contained alizarin

and purpurin or just one of the two dyes but no other dyes. Both

components were detected in seven samples, a brown silk satin

(CgAf-2:126469), three brown wool twills (CgAf-2:101991,

112648, 124990), a brown wool tabby (CgAf-2:101202), and

two green brown wool twills (CgAf-2:124957 and 124995).

Purpurin, but not alizarin, was detected in a green wool (CgAf-

2:109810) and a dark red brown wool (CgAf-2:127320) that also

contained gallic acid. Alizarin was detected in 109020, a brown

wool twill that contained some red fibres.

The hydroxyl flavoneluteolin was identified in seven fibre

samples: three green silks (CgAf-2:78130, 87101 and 124904);

three brown wool twills (CgAf-2:67517, 78130 and 148115);

and one yellow wool twill (CgAf-2:124994). Luteolin was

detected in two samples from artifact CgAf-2:78130, one brown

wool fragment from a jacket, and the other green silk from a

button hole.

Logwood was present in two black wool samples with a twill

weave (CgAf-2:97640 and 230445). Chromium was detected by

x-ray microanalysis in the same samples and alizarin was also

detected in CgAf-2:97640. Logwood was used as a substitute

for woad, and though fugitive, produced a purplish blue [56].

Because of its fugitive nature, this dye was banned in England

until a method for making it fast was introduced in 1605 [57].

This dye could therefore have been used to produce a black or

blue cloth [58].

The dyes identified include those common to the period.

Madder was the most common dye after woad in the 17th

century [59]. Not surprisingly therefore, madder was identified

on more samples within the Ferryland collection than any other

dye compound. Cochineal, an expensive dye, was identified only

on the silk fragments. Madder and weld were identified on both

wool and silk. Weld, or dyer’s weed, was one of the major sources

of yellow [60]. Logwood dye was identified on wool. Samples

which tested positive for tannin included 15 wool and 11 silk

fragments. Samples which tested negative for dyestuffs included

nine wool samples. Un-dyed wool was not uncommon at this

time and it is therefore unsurprising to find some wool samples

without dyestuffs, although this may represent leaching by the

soil matrix. Though tests for blue dyes were performed none

were found, apart from the 18th century Prussian blue.

An overall view of the textiles based on the results of dye

analysis indicates that textiles were coloured either red or

yellow. It is difficult to speculate as to why there was a preference

for red and yellow at Ferryland. Cunnington cites a reference

to the wearing of blue at this time, to be used for the dress of

apprentices and servants [61]. If this is in fact true, it might

suggest that the Ferryland privy was used only by gentry. Or it

could simply be that supply ships did not go to areas where bluedyed

textiles were manufactured. Kerridge notes that Suffolk

cloths were a true blue in the wool. Here woad and indigo dyes

were used to create a range of shades [62]. Neither cloth bale

seals nor other material culture excavated at Ferryland, to date,

indicate a trade link with Suffolk. Woad was not grown in large

quantities in England until the 1560s [63]. Though both madder

and weld were grown domestically, most of the madder was

imported from Flanders and Zealand [64]. Other dyestuffs were

imported, gall-nuts (used to fix logwood) from Venice, cochineal

from Central and South America, and logwood from the West and

East Indies, Central and South America and Virginia [65].

The high percentage of tannin identified along with the two

logwood dyes might allow one to speculate that these represent a

black or blue dye. Aluminium and iron elements identified could

represent mordants used to make the dye fast [66]. The absence

of woad or indigo, within the collection may be explained by the

fact that logwood was used to produce blue.

Extant costume provides further evidence of what was

available for English consumers in the 1600s. Based on this

evidence, and the fragments found at Ferryland, one may

think that costume was used as an identifier of status in North America to the same extent as it was in England. The question

as to whether or not costume was used as an identifier of

social change in the colonies is much more difficult to address

because of limited accounts of society there. Excavations at sites

comparable to Ferryland, such as Jamestown and St. Mary’s

City, are not yet complete; archaeologists and anthropologists

continue to investigate and interpret social changes through

the analysis of artifactual and structural remains. The changes

that occurred at Ferryland are as follows: documentary records

indicate that Sir George Calvert initially ran the early colony as

a co-operative venture from 1621 to 1634; but when Sir David

Kirke and his family arrived in the late 1630s, the colony’s cooperative

nature changed to an entrepreneurial one where taxes

were levied.

The price of cod and its abundance fluctuated throughout

the 1600s and the colony was attacked by the Dutch in 1673

but continued until the French attack of 1696 [67]. It seems

that from about 1640 to 1670, the colony at Ferryland, under a

capitalist vision, experienced a significant gain in wealth [68].

Potentially, the colonists had greater buying power during this

time. Boats were coming and going more frequently which made

it possible for costume-related items to be readily available at

Ferryland. Based on links between Newfoundland and English

ports, drawn by Pope, an estimated 86 boat crews from Jersey,

London, Southampton, Torbay, Dartmouth and Plymouth may

have brought goods to Ferryland in 1675 [69]. Therefore, the

same social changes that came with the Reformation in England,

and the associated changes in costume such as rich textiles,

ribbons, expensive dyestuffs, could have been seen at Ferryland.

Textile remains support this interpretation.

From inventories and cargo manifests, one sees that there

was a consistently high demand for alcohol and tobacco among

the colonists at Ferryland; likewise, there was demand for bolts

of woollen cloth [70]. What did the consumption of luxuries

such as wine and tobacco say about the men and women who

lived and worked in 17th -century Ferryland? It could mean that

if they could afford luxury grocery items to be consumed in

Ferryland, then they likely had and consumed luxury costume

and household goods as well.

Weatherill argues that the material culture associated

with domestic life was closely linked to the practical everyday

lives of the household and it is within this everyday existence

that one will find the meaning of consumption [71]. Most

archaeologists would agree that the objects recovered from a

house structure reflect the main activities of that household.

Therefore, an understanding of consumption patterns could be

gained through the examination of excavated objects. One could

assume that costume and household textiles would offer similar

insights. In considering patterns of consumption for Ferryland

in the 17th century, one must be cautious however, because the

fragments analysed in this dissertation are discarded materials.

The time lapse between use and discard particularly for the

specimens from the privy could change the interpretation of

past consumption patterns.

There would have been goods consumed that did not

wear-out and were therefore not disposed of. Both the privy

contents and those from middens do provide us with hints

of the goods that came to Ferryland, either with the colonists

themselves or on ships as trade goods. Costume can be viewed

as an object of necessity in that it serves to protect the body

from its surrounding environment. Unlike a bowl for consuming

food which may or may not be absolutely necessary, clothing

became not only a consumable with practical meaning, but also

one which could be used to identify an individual. Textiles as a

commodity are personal products. For centuries, they have been

used to drape the body, wrap the wearer, seductively or modestly,

for public viewing; textiles likewise can be used as swaddling

clothes at birth and a shroud at death [72]. Because fabrics are

woven, flat and generally absorbent, they have also served as

a substrate for applying decoration via embroidery and colour

via dye compounds. In this way, an applied decoration or colour

could become a cultural signifier or emblem of status. One must,

however, first determine whose culture is being interpreted. For

example, the motifs on 16th-century Spanish silks, which were a

blend of Chinese and Islamic symbols, influenced silk production

in 17th-century Europe and England [73]. During the 17th

century, the French, dominated the silk industry, but the English

silks became popular at the end of the century. Examination of

extant textile reveals the incorporation of foreign motifs and

designs into European culture [74]. Manufacturers, wanting to

please their clients, also blended traditional textile designs and

motifs to suit the tastes of European customers [75].

By the end of the 17th century, because of demand, much of

Asia’s goods for export were mass-produced; a similar trend

occurred in Europe. This included pottery, fabric and gowns.

Thus, because of the desire to mass-produce goods, the motifs

on silks became blended and adapted to fit with this need and

ideology of rapid manufacture. Elements which might have

been distinct to the Tang dynasty or of Islamic origin were

stylized and attributed to the French or Spanish cultures. For example, within the ceramic remains at Ferryland, we see the

incorporation of Islamic design on Portuguese ceramics (Figure

8). Other imported goods, such as Chinese porcelain, are also

visible evidence of different cultures. Porcelain represented the

high status of the owner of such items. One piece of high-quality

porcelain, CgAf-2:377874, probably a tea bowl with base and

rim section, was excavated from an early 17th -century context

in the Kirke house.

By the late 17th century, England’s economy had changed yet

again with the wealth of the country being shared among those

of the middling sort. This ultimately meant that luxury goods

found a wider consumer group still further down the social

ladder [76].

For example, a hair comb, CgAf-2:508922, found in the area

of the Kirke house could have been owned by one of the lower

sort working or doing business for the Kirke’s (Figure 9). By the

1600s goods from different parts of the globe were being traded

within Western Europe. This practise became fairly standard

by the end of the century. At this time, the less expensive exotic

goods were available to the general population.

Exotic goods such as tobacco, tea, chocolate and coffee also

were consumed by everyone. These commodities, however,

were consumables, though for some, additional props would

be added to the ritual of consumption, for example tea drinking

rituals complete with table settings or the tobacco pipe for

smoking. Therefore, consumable commodities generally did

not have a lasting life. They were visible in the course of their

consumption but then they were gone. For the consumption of

tobacco, coffee and tea, an addiction could develop, and a routine

of consumption created. In this example the consumption of the

commodity would be visible but not always constant [77]. The

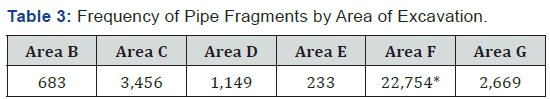

large number of tobacco pipe fragments, excavated at Ferryland

(Table 3) provides evidence of extensive consumption of tobacco,

a luxury grocery at Ferryland. Textiles by contrast, would be

a more visible commodity either worn on the body or as part

of the domestic space as curtains, bedding and pillows where

decoration and colour potentially would have a greater meaning.

16,000 fragments were recovered from the “Kirke House”.

The 17th century was a period of increased consumption

of commodities by the middling sorts and to a lesser degree

by labourers. As noted by Wetherill, in her study of window

curtains from 1675-1725, consumption patterns are not

predictable because factors, such as availability and differences

in sensibilities, are difficult to determine. In the case of window

curtains, a luxury good, the highest percentage of curtains were

found among the middling sort followed by the gentry [78].

The material culture, excavated from the middling domestic

structures, such as Areas B and D, support this observation made

on the basis of probate documents [79]. Documentary evidence

shows that the population at large was aware of the link between

providing evidence for ones social life through consumer goods

[80].

In 17th-century England, the household was still, in most

cases, the site of both production and consumption [81].

Changes in demand within the textile industry resulted in

changes in production. The increased popularity of the New

Draperies which required finer worsted wools, dyes and broader

looms took the industry out of the home and into a central, often

urban, area [82]. This change has afforded better records for

researchers to examine. Therefore, a better understanding

of what was available to purchase at this time was garnered

through the factory records. Understanding what was available

to those in North America is much more complicated. Firstly,

records specific to consumption of goods in North America seem

limited. Probate inventories did not always survive as they were

initially sent back to London for storage. For most of the 1600s

consumerism in North America was dependant on the rate

of trade between the America’s eastern seaboard and Europe.

References to clothing were not always recorded [83].

We may not know exactly what the nature of textile

consumption was for Ferryland, because of the lack of

preservation of textile remains and a paucity of historic

documents, but because it is clear that textiles were not produced

in Ferryland and therefore had to arrive by boat, we can look

for other evidence of foreign textile consumables. These foreign

consumables were shipped on vessels which most likely held

bolts of cloth and ready-made goods as well. For our purposes

the presence of the New Groceries, tobacco, sugar and caffeine

drinks, can be used to indicate the availability of consumables at

Ferryland and wealth of the colony.

Within the archaeological record, the tobacco clay pipe is the

most ubiquitous of all items used to consume the New Groceries.

Tea bowls or mugs can be used to indicate the presence of

tea or coffee, but these could be used for other fluids at times

when the intended drink was unavailable. We know from both documentary evidence and archaeological examination that

neither tobacco, sugar cane nor cocoa beans were grown in

Ferryland; these plants simply could not grow in Newfoundland’s

sub-artic climate [84]. Because of this, the presence of tobacco

pipe fragments is directly related to the importation of tobacco

to the colony. Therefore, an examination of clay pipe fragments

from the Ferryland site, used as an indicator of the availability

of tobacco, can likewise also demonstrate that ships coming to

the colony brought goods for trade and not just to pick up dried

cod to return to European ports for sale. An examination of clay

pipe bowls is therefore used here to give an overall idea of the

extent to which the relatively new habit of tobacco smoking

was adopted by the people of Ferryland. The clay pipe was in

use from the early 1600s to the 20th century. As a dating tool,

however, clay pipes changed stylistically and often had a datable

maker’s mark applied, which allows it to be used to date strata

in the archaeological record [85]. It is not within the scope of

this thesis to examine all pipe bowls to separate early ones from

later ones. As shown in Table 3 this would require a significant

amount of work, some of which has been done by past MA

students at Memorial University [86]. For this research, the

presence of the early pipe bowls at Ferryland is evidence of ships

bringing tobacco and, potentially, other goods such as textiles.

All of the material remains found at Ferryland were

manufactured off the Island. The artifactual remains,

approximately 1.5 million to date, are too numerous and

varied to represent objects merely brought to Ferryland by the

colonists. Though some of the material found was no doubt

brought by families, most represent objects of trade. There were

three means by which trade goods reached Ferryland, the sack

ships (20-80ton vessels), the fishing ships (50-130ton vessels),

or by the practice of portage [87]. The sack ships which sailed

to Newfoundland in the summer to buy fish from planters or

buy-boat fishermen (inshore fishermen) were likely the source

of most foreign goods [88]. Portage was the right of a sailor to

carry goods to a particular location for the purpose of re-sale.

This was allowed in lieu of wages [89]. Smaller items such as

textiles and costume-related material were likely transported to

Ferryland by this practice.

While viewing textiles at the Victoria and Albert museum, a

selection of wool textile fragments from the Museum of London

were examined. These textiles, representing fabric fragments

discarded in the Thames, were similar in weave to some from

Ferryland. These fragments from the Thames were broadly

dated to the 16th and 17th century and 70% of them were New

Draperies. This confirms that New Draperies were readily

available in London currently.

The madder identified in the Ferryland samples also tested

positive for alizarin [90]. This is considered typical for wild

madder Rubia Peregrina which contains 11% alizarin. Another

discovery in the Ferryland collection, is that madder and

cochineal were mixed to form the colour in many of the silks

[91]. Samples which tested positive for tannin included 15

wool and 11 silk fragments. Samples which tested negative for

dyestuffs included nine wool samples.

What do the small finds tell us about life in Ferryland?

Researchers believe that shoe buckles began to be used during

the last quarter of the 17th century [92]. Within the Ferryland

collection shoe buckles are present at about the same time.

Approximately 30 two-piece buckles, no two alike, which may

have served as shoe buckles, were found at Ferryland contexts

from the second half of the 17th century. Three of these were

made of silver, the others of a copper alloy. For a colony with

a population of some 150 people, this could mean that 20% of

the population was wearing buckled shoes by the second half

of the century [93]. Only three two-piece buckles were found at

St. Mary’s City and no buckles of this type were found at Cupids.

This suggests that shoe buckles were more available to Ferryland

and that colonists had sufficient money to buy them.

Coins likewise contain information about costume [94].

One Ferryland coin depicts a falling linen collar. This coin, CgAf-

2:298218, is identified as French and dates to the 1630s [95].

Where exact dates are lacking, items of material culture which

incorporate costume from extant or archaeological examples

can be used to confirm dates. For example, a similar collar at the

Gallery of English Costume, Manchester, M7755, has been dated

to the 1620s-1630s which coincides with the date assigned to

the coin. Likewise, tin-glazed ceramics of the 17th century also

incorporate figures dressed in costume of the period. Where

archaeological samples may lack an exact date, the costume

depicted can be used to provide an estimated date. Like printed

images, however, one must assume that the costume depicted is

contemporaneous with the object’s date of manufacture.

Self-importance based on the public image one created was

significant during the 17th century. The nobility, gentry and

middling sorts strove to be up-to-date with the latest fashions as

observed in documentary evidence, paintings, prints and extant

costume. The archaeological remains, which usually provide an

accurate reference for dating, also support this observation.

The growth of venues for public gatherings such as the coffee

houses and taverns also contributed to the growth of this display

culture. People were out in public and wanted to be seen at their

best. No longer was the home the only showcase. While in public

view one’s attire would provide a visual image of their place

in society. The growth of print culture also drew people into

public venues. The number of pamphlets produced in England

grew from 22 in 1640 to 1,966 in 1642 [96]. Coffee houses were

popular and available to all. Here broadsheets could be read and,

in some cases, read to an audience. Here was a place to acquire

knowledge of the current events.

Some of the questions answered here touch on the

traditional themes of historical costume studies: the textiles’

poor preservation; incomplete archival records, such as the undocumented exchange of costume goods; and an incomplete

depiction of life in the contemporaneous visual record. Extant

documentary records from the 17th century should be further

explored to reveal additional information regarding costume.

Further aspects of the adaptation of costume should also be

examined. More work could be conducted to identify evidence

of dye plants being grown in 17th century Ferryland. In addition,

evidence for sheep herding and weaving could be examined.

On-site excavations at Ferryland and continued analysis may

uncover some of this information. For example, does the quality

of textile remains increase when the Mansion house is found?

If the cemetery associated with the site is uncovered, and if

its contents are well preserved, one might gain information

regarding the quality of complete costumes. With further

excavation, the distribution of people in their living quarters

may be revealed. Did the colony always have a resident tailor?

Was there more than one at any time during the 1600s? Further

excavation could reveal a storehouse of cloth and other supplies

used by a tailor. All of these questions could lead to a greater

understanding of the independence and co-dependence of

Ferryland’s 17th-century population in relation to England and

Europe in reference to costume.

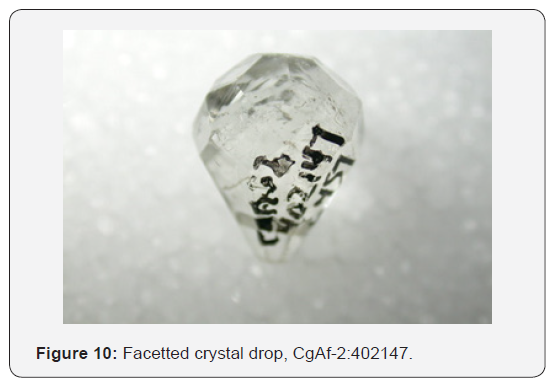

Seventeenth-century England could be characterized as

being a time of internal turmoil [97]. It was also a period of

colonization of foreign lands and an increase in technological

advancements. For example, the facets cut on a crystal drop,

(Figure 10) CgAf-2:402107, would not have been possible in

the previous century. Perhaps both the conflict within England

and a desire by the nobles and gentry sorts to explore outside of

England lead this nation to succeed in the transplanting of people

to places such as Ferryland, Newfoundland. The Calverts and

Kirkes left England for a more peaceful existence in Ferryland.

Outside of the reaches of parliament and the monarch, this

colony flourished, possibly because it was less affected by the

politics of the time.

In terms of costume for the Ferryland site, we are questioning

whether the growth in fashion in post-Medieval European

populations was carried over to those colonizing North America.

Could regional differences be identified, in this case, between

England and the Colony of Avalon? Did changes in fashion and

culture in England also occur in Ferryland? If so, was this at the

same rate or was there a time lag because of distance form the

cultural hub of London? Do we see signs of adaptation in terms

of costume this early in the historic record?

The small finds, which constitute the associated costume

components and the fragile organic textiles often don’t survive

because of the aggressive nature of the burial environment;

hence the cold, moist environment of Eastern Canada aid in the

preservation of some significant textile finds.

The degree of artifact preservation does make predictions

of culture difficult. The non-ferrous metals used to produce

the buttons, buckles and other costume components are

well preserved at Ferryland. One can therefore draw some

conclusions about the status and general standard of living based

on what has been preserved. One must, however, be cautious and

mindful that the colonists relied on what they brought with them

and what was available on the sack ships and fishing ships that

visited Ferryland’s harbour. To date, the bulk of the textiles, have

come from a privy feature which provided an almost anaerobic

moist environment sympathetic to their preservation. These

fragments, however, represent re-use; although this serves as

evidence of the types of fabrics used at Ferryland, their dates

are poorly defined. We know that the privy was in use from the

1620s to the 1670s and that it contained a high proportion of

the New Draperies. During the 17th century privies were usually

used only by the gentry sorts. The group of textiles found in

the Ferryland privy generally support this. The Nanny privy in

Boston also contained fragments of luxury textiles; this privy

was associated with a high-status household of the late 17th

century. Though the dates of each privy do not correspond, for

comparative purposes textile and costume pieces made their

way to North America throughout the 17th century. It appears

that this is the case for English settlements early in the century.

The contents of the privy are the most significant repository

for textiles. The textiles are divided between tailor’s scraps made mostly of silk and square fragments of wool used for

hygiene purposes. The former represents the gentry and the

contemporaneous creations of a tailor. The latter represents

reuse of worn or out-of-fashion clothing items. One might

also divide the contents by their quality and cost with silks

representing greater luxury than the wool. Overall, however,

given the large quantity of the New Draperies, the dyestuffs

used, and weave structures, it appears that the colony was not

poor, but instead offered a high standard of living for all. Another

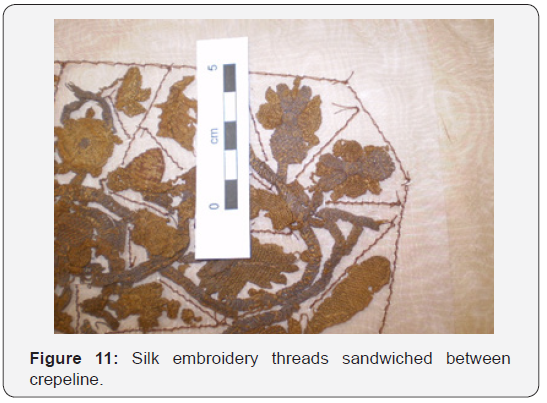

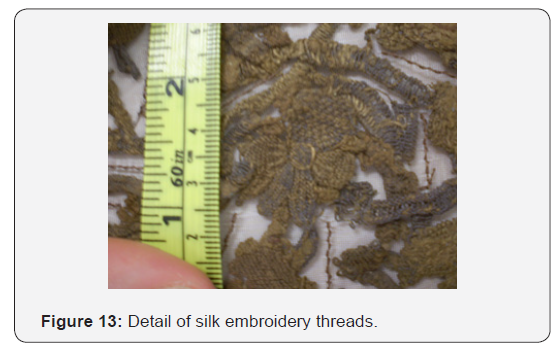

collection of textile fragments was a lump of embroidered

threads on a silk substrate. When unfolded, cleaned with

water and freeze dried this lump seems to resemble a women’s

embroidered jacket dating to 1620 on exhibit at the Museum of

Costume in Bath, England. Figures 11-14 show some of these

embroidered threads.

In a broad sense, historians and archaeologists have

examined the colonisation of the New World in the early modern

period to document adaptations to a new environment, the

transfer of Old World ideas and technology and the invention of

new solutions. This thesis further contributes to this research.

Differences in the Ferryland privy with its high wool content and

the Boston privy where silk was dominant may provide evidence

of adaptation by gentry to the cooler climate of Ferryland. The

material culture found at Ferryland, in terms of both costume

and non-costume related goods, indicates that there was a rapid

transfer of commodities from Europe. This is not surprising

given the volume of shipping essential to the region’s cod fishery.

The fact that boats came to Ferryland did not necessarily mean

they would bring commodities for consumption. This would

have occurred only if there was sufficient wealth to pay for such

goods. The overall quality of material culture found at Ferryland

supports the notion that there was indeed essential wealth to

bring in such goods. Did those living in 17th century Ferryland

attempt to emulate their English domestic environment? Overall

building construction, though not as grand as that found in

England, appears to be based on English styles [98]. The rise

of the middling sort is of importance here as the archaeological

evidence at Ferryland clearly indicates the presence of middling

and gentle folk. The middling sort comprised a newly-defined

social group in the late-seventeenth century [99].

Though the items of jewellery found at Ferryland are

relatively few, the range in quality and value from middling to

gentry, which fits nicely with the range in status of those at the

colony. Moreover, most of the items of jewellery available in the

17th century is represented at Ferryland.

Conclusion

An examination of textile, jewellery, buttons and buckles

along with the ceramic assemblage from Ferryland clearly

indicates that many colonists had wealth and brought some

fancy items with them. This contrasts with the colony’s gentry

buildings which were in general smaller and less extravagant

than homes of the gentry in England [100-136]. At a time where

visual presentation was important, this is one aspect of the

Ferryland colony that fits poorly with activities back in England.

Captain Wynne and other colony managers had a vast quantity

of building materials available to them in the surrounding

area. Perhaps a knowledge of piracy in the area influenced the

building style to such a degree that the colony was purposely

built as a middling settlement and therefore not worth the effort

of attack. Costume could be displayed or hidden on demand. It

appears that the people of 17th -century Ferryland used personal

belongings and costume to identify their status [137-180].

What is certain at this point is that William Sharpus, a tailor,

arrived in Ferryland in 1622 to practice his trade. From excavated

bale seals, we know that cloth was sent to and unloaded at

Ferryland. Given the presence of a tailor, one would expect to

find some archaeological remains to support this occupation [181-210]. Numerous thimbles, pins, scissors and scraps of

cloth have been found, all of which support the presence of this

activity. This may be one indication of self reliance on the part of

this community of some one hundred and fifty souls.

The print culture studied here provides further evidence

and support for the material culture found at Ferryland being

from the 17th century. Each dated print contains a fragment of

costume detail from the past, such as buttons, hats or shoes,

which have been found in the 17th century context at Ferryland

[211-238]. Though there is little more that can be said here, from

an archaeological point of view this conclusion is significant.

Because the burial environment is not a complete picture

of the past, many mis-interpretations can be made. The 17th

century print culture represents a resource yet to be utilized by

archaeologists.

Through the one hundred years of textile finds from

Ferryland, Newfoundland, there were many changes in the

textiles and related artifacts from the course Old Draperies to the

finer and softer New Draperies and from ties to covered wooden

buttons to cast metal buttons. The footwear gained height with

heels, shape and colour with dyes. The hats went through many

stylistic changes, but also material ones from knitted woollen

caps to tall shaped beaver hats. A man’s costume developed into

one which included breeches, vest and coat – the suit which is

still worn today, though appearing somewhat differently in style.

The 17th century was a time of many political, environmental

and economic changes. The English colonized new lands and

continued to grow as a world empire. How people perceived

themselves and how they dressed themselves to be perceived by

others could not help but change in such a climate. The century to

follow would bring even more elaborate costume as the country

continued to grow. It was, however, the great expansion of

Europe through colonization, (Figure 15-17) in the 17th century,

of which Ferryland, Newfoundland was an important part, that

set the path for the 18th century.

Comments

Post a Comment