Psalteries of the Royal Door Gate (1144) of the Cathedral of our Lady of Chartres- Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Opinion

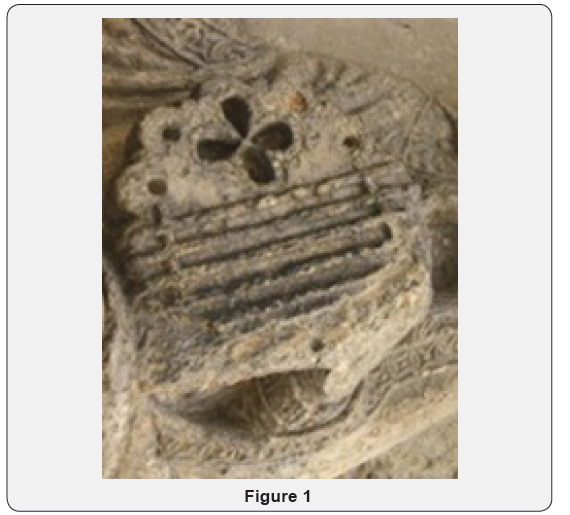

In the south door gate of Chartres Cathedral, called

Royal, there are four depictions of Psalteries. The first instrument,

very damaged, has 5 strings passing over two almost parallel bridges

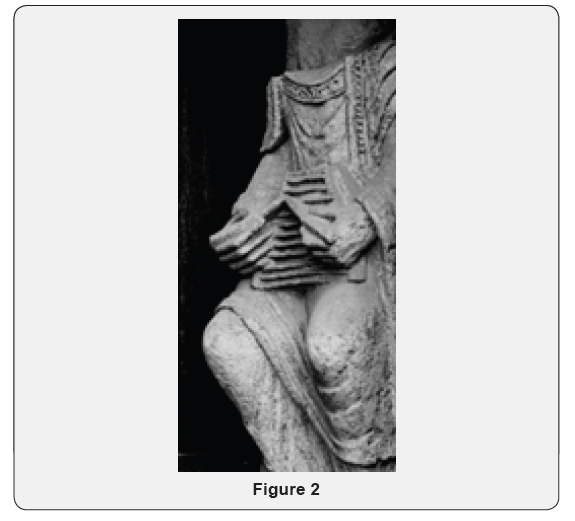

(Figure 1). The second psaltery has ten strings, the angles between the

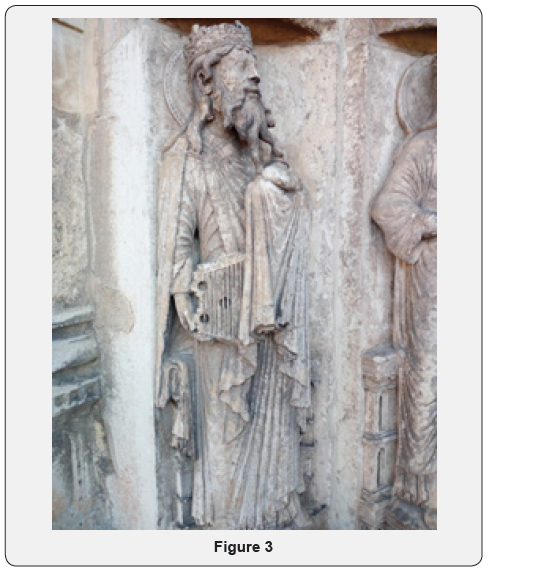

bridges and the strings being of 72° (Figure 2) The two main psalteries,

that of the first Elder of the Apocalypse

(Figure 3) and that of the Music (Figure 4), share the same structure:

nine pairs of strings form with the bridges a regular trapezium, the

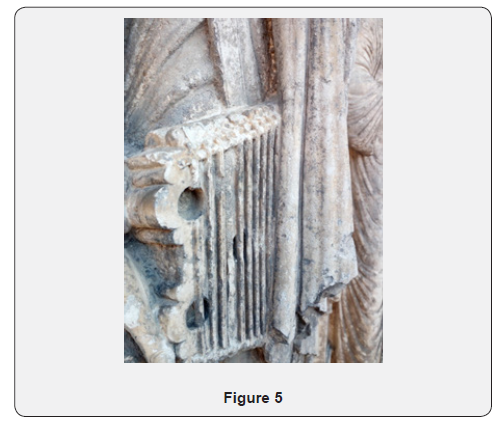

angles at the base of 72° [1]. The first psaltery has a tenth pair of

strings, well hidden under the mantle of the Elder, invisible from below

(Figure 5). The other psaltery has nine pairs of strings, although

there would be room for a tenth (Figure 6).

In contemporary texts the name Psalterium decachordum,

from the Old Testament, Psalm 32 is frequently used. Saint

Jerome (Epistula ad Dardanum) states that the adjective

decachordum refers to the moral law: the Decalogue. One

wonders why to represent with nine strings instruments which

as usual had ten, in addition to put them in great evidence in

the hands of the first Elder of the Apocalypse and in the allegory

of the Music represented among the Liberals Arts. To answer

this question, one must consider the different points of view of

the medieval public. Illiterate visitors see instruments and do

think about Celestial Music. The illiterate musicians recognize

the instruments and perhaps count the strings: they think of an

error or a novelty in the music. Visitors trained into the Liberal

Arts know that the Nine can have different meanings. The

Orthodox Catholic vision as the successor of Isidore de Séville,

considered the Nine to be imperfect compared to the Ten (Liber

numerorum qui in sanctis scripturis occurrunt 10.52.PL 83: 190).

In this case, the nine strings could be related to the imperfection

of our musical knowledge, mentioned by Musica enchiriadis (XIX,

10-12) and Micrologus (XIV, 16-19). Pythagoras, who was sitting

close, had stated the perfection of Ten in Tetraktys. Nevertheless,

in musical tradition the Nine, in the fundamental ratio 9/8, is

considered “omnium musicorum sonorum mensura communis”

(Boethius, Arithmetica 2,54, CCL 94 A: 224). 9/8 is the

fundamental cosmological ratio in Plato’s Timaeus, whose ideas

were transmitted by Cicero, Macrobius and Calcidius. Marcianus

Capella affirms that number Nine “harmoniae ultima pars est”

(Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii 7.741). In the twelfth century

Magister Johannes of Seville in his Liber Alchorismi de pratica

aritmetice, translation of the lost book of Muhammad ibn Musa

al-Kwarizmi, introduces the Indian numeration. He explains that

“ergo constat unumquemque limitem 9 numeros continere”, he

recalls that nine are the celestial spheres and nine the angelic

choruses [2]. William of Conches in his work Philosophia gives

no importance to the Ten, while nine are the invisible circles

of heaven (Liber II, V, 13) and nine months of human gestation

(Liber IV, XIV, 22-23). Finally, the most awesome visitor could

have observed that the ratio between the first and the last pair of

strings (hidden or virtual) is 3/2, the right Fifth, the fundamental

harmonic ratio in pythagorean musical theory. Thus, the learned

man could interpret the nine strings of the psalteries as a symbol

of the foundation of harmonic science and at the same time of

the imperfection of our musical knowledge.

To know more about Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment