Boot Spurs: A form of Accessory or a Tool?- Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

For researchers of Art History or Archaeology of the

Early Modern Period evidence must be multidisciplinary in order to

understand all aspects of culture. Objects which become popular as a

costume component can serve as markers for change in culture. This paper

will demonstrate the value of one such marker, the boot spur of the

17th century. Examples are taken from an archaeological site in

Ferrlyand Newfoundland and the British Museum. Of note here is an

additional limitation when using this type of research material and that

is the burial environment. Depending on the nature of the material of

manufacture even the burial environment will not necessarily tell the

whole story as some objects will survive burial and others will not. The

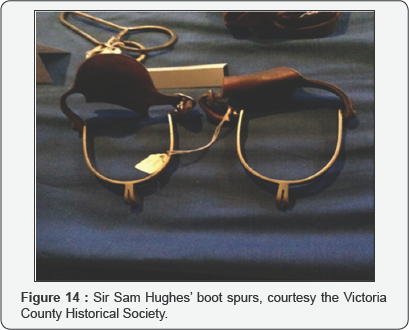

boot spur re-surfaces as an important item of dress in the 1900s. One

such pair belonging to Sir Sam Hughes, General of Canada's Military in

the First World War, shows more detail, because they have not been

buried, but are of a similar style.

Keywords: Boot spurs; Archaeology; Ferry land

Introduction

This paper will describe the boot spur of the 17th

century and then compare this to one from the 20th century. This

element of costume for the 1600s was both functional and iconic to the

wearer. The boot spurs described are from archaeological contexts with

one area being at Ferry land Newfoundland and the second having no

provenance but has been collected by the British Museum collection. The

17th century boot spur was an expensive piece of

horse-related hardware; often with gold or silver gilt on a base metal

of brass or iron. Thus few owned this object type and therefore it is

rare to find these in the archaeological record. It is also rare to find

these objects given that metals do not survive well in the burial

environment. Thus the objects presented here are unique within the

context of global museum collections. I therefore encourage researchers

and students to further explore the genre of boot spurs from the Early

Modern Period. Both collections are accessible by the public. The boot

spur from the 20th century is accessible to the public via the Victoria

County Historical Society.

Metals used for the Boot Spurs found at the 17th century colony in Ferry land

During the 1600s, from the perspective of material

culture found in the archaeological record, it would appear that iron

metal was an important base metal with gold, silver and tin being

important metals for surface decoration. For example, boot spurs from

the period were largely made of wrought iron as was a small decorative

personal item such as snuff boxes. That said if this site represents

much of the 1600s globally then our interpretation of jewellery is very

much determined by burial environment as metals and in particular iron

metal is susceptible to degradation in most global burial environments. Figures 1-2

shows a range of personal adornment object types found at the Ferry

land site. The best type of soil matrix for metal preservation is one

which is dry and or drains easily. Thus high sand and loam

concentrations are best allowing for drainage of ground water or

precipitation. Such an environment is found at the archaeological site

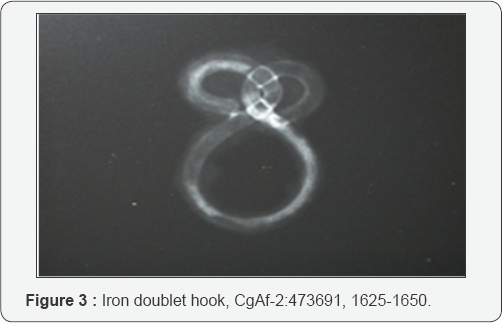

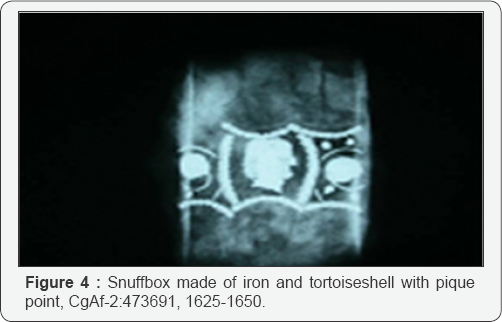

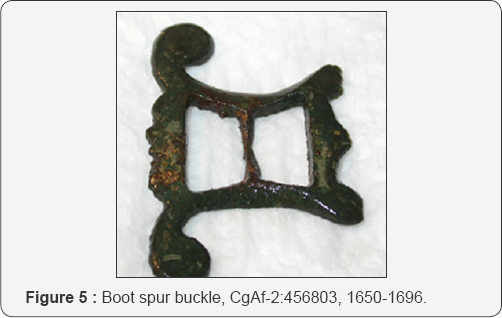

in Ferry land Newfoundland. The doublet hook made of iron shown in Figure 3 is one of a few of this object type which has survived. That is why fragile objects (Figures 4,5), not usually found in an archaeological context give a different view to the 17th

century simply because they have survived while most have not. This

site, being untouched for centuries, provides excellent context for

understanding the evolution of material culture for the Early Modern

Period. The 20th century spur is made from a copper alloy likely brass

and leather.

Changes of Style

One of the most useful aspects of costume to

researchers is the change in style over time. This change facilitates

the use of these artifact types for dating purposes. If found with a

known context in the archaeological burial environment, this object type

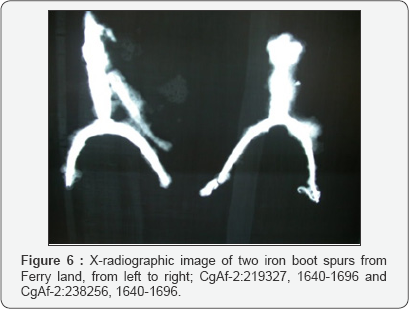

can aid in the interpretation of the site, for example (Figure 6-8).

That said, from the work of art historians we know that costume style

changes can be a useful tool for presenting aspects of cultural change

and or comment. Thus the style might represent the 1620s but be used in

the 1720s as a commentary of current cultural change. Similarly because

these objects generally have a higher monetary value they are kept and

passed along to others thus the context in which they are found can

represent other aspects of culture beyond ownership. These facts added

to the degradation of the burial environment make any positive

identification or matching of artifacts between institutions of great

interest. The following description of the archaeological site provides

context to the Ferry land boot spurs.

The Site

The areas of excavation relevant to this discussion

include three areas of domesticated structures and one of a waterfront

warehouse. Costume-related artifacts recovered at the waterfront area

are predominantly small finds such as buttons which could have easily

been lost from garments worn within this working area of the site.

Overall the waterfront appears to be early 17th century. Domestic structures dating to the second half of the 17th

century and have been described as houses occupied by residents of the

middling class by Nixon and Crompton, respectively, and the associated

costume-related material culture generally supports these conclusions [1,2].

Though three woollen button holes, found in the area described by

Crompton, with silver metal threads, CgAf-2: 78983, are an exception, in

that they appear to be early 17th century. These objects are

in themselves odd because of the fact that they had been cut out of

their original garment for recycling is indicative of a status below

that of the gentry. This also could explain the discrepancy in date.

Overall though useful costume related objects used to provide context

can be extremely problematic. Possibly the most elite of the domestic

areas, described by Tuck and Gaulton [3], dates to the second half of the 17th

century. This area has supporting luxury goods such as tin-glazed

ceramic vessels and terra sigillata earthen wares. Additionally from

this area six pipe bowls bearing the initials "DK", and a lead "DK"

token were found making researchers believe this to be the residence of

Sir David Kirke, proprietor of the "Pool Plantation" from 1638 to 1651 [3].

Fancy objects of costume were found in this area, including two gold

rings, silver-plated iron boot spurs, a silver thimble and bodkin, and

numerous tin-plated copper pins, and this possibly provide sufficient

evidence to confirm that this was the primary Kirke residence in 17th

century Ferryland. The boot spur evidence from this area will be used

here to compare to boot spurs in the collection of the British Museum.

The 20th century boot spur was never buried and stored in domestic enclosures.

Comparison of the Ferry land Boot Spurs with the British Museum Collection

A survey of 31 17th century boot spurs in

the collection of the British Museum, London, was undertaken to identify

stylistic changes through the century. Unfortunately, few samples had

precise provenance, with the majority simply identified as being from

the 1600s. A possible place of manufacture could have been Milan [4].

Stylistic differences in the rowel (rotating star section), terminal

(section of loops or hooks allowing boot spur to be attached to boot),

and pole (metal shaft onto which the rowel attaches) orientation were

identified within the British Museum and Ferry land collections and are

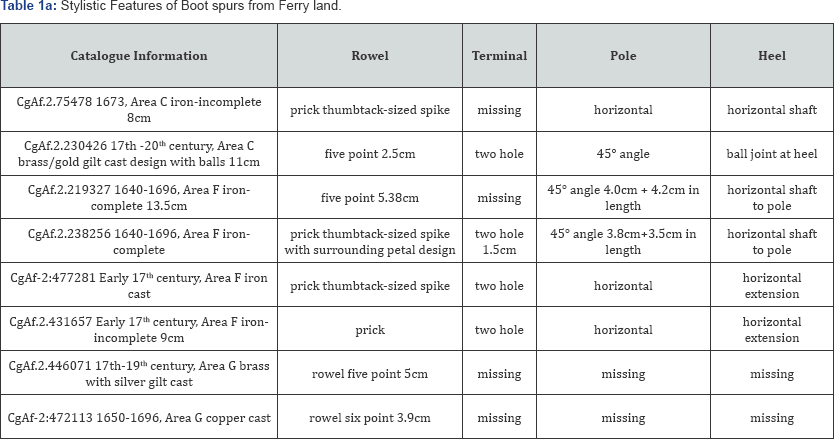

summarized in (Table 1a & 1b).

The Ferry land collection holds eight individual boot

spurs. Five of these represent either complete or fairly complete boot

spurs while three examples are only the rowels. Each of these shows

evidence of wear and each was likely discarded because it no longer

functioned properly. Each displays stylistic and material variation. The

first brass and gold gilt boot spur (CgAf-2:230426), (Figure 9)

with its 2.5cm, five-point rowel resembles British Museum objects

AL116/400 and AL116/404. The first British Museum example was assigned a

date range of 1600-1660, while the second probably dates to the 1630s

and certainly fits within the 1600-1650 range. The Ferryland example was

found in a deposit associated with the Kirke house (1640s-1696).

Ceramic sherds from this midden have also been identified as wares from

the first half of the 17th century [5].

The examples identified in the British Museum collection, as well as

the archaeological evidence, indicate that this particular boot spur can

be assigned a date range of 1600-1660.

Bold text = components of both iron and brass spurs which may match with Ferry land spurs

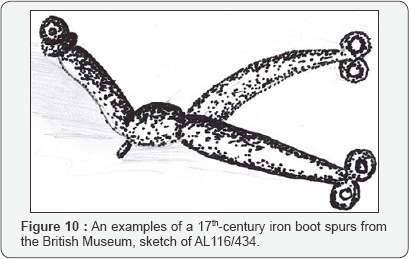

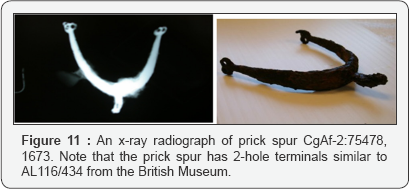

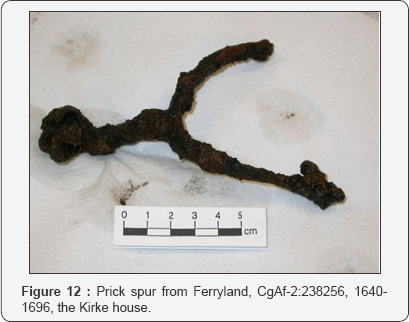

Iron boot spur fragments from Ferryland could match with those from the British Museum as follows (Figure 10). Figure 10is a sketch of a boot spur from the British Museum showing the terminal ends. X-radiography of artifact CgAf-2:75478 Figure 11 has similar terminal ends. Figure 12-14 shows a prick spur CgAf-2:238256 which date to the mid-17th

century. These boot spurs resemble boot spurs AL116/411, AL116/434 and

AL/463 from the British Museum. Objects AL116/434 and AL116/416 date to

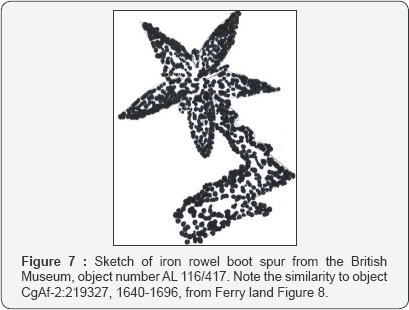

the mid-17th century while AL116/411 dates to the late 17th century. British Museum samples AL116/409, AL116/416 and AL116/417 are similar to iron boot spur CgAf-2:219327 (Figures 4-6), dating to the mid-17th century.

Noёl Hume suggests that during the first half of the 17th century boot spurs were mostly made of iron [6].

Brass spurs were also used at this time but tended to be very fancy

with elaborate chased design and gold gilt. They had large rowels and

elbowed shanks and poles. The most common type of boot spur had a

straight shank with a small thumbtack-sized spike or prick instead of a

rowel. Based on the boot spurs recovered at Ferryland, it seems likely

that object CgAf.2.238256 was made of iron and was used by someone of

the middling sort while the fancier brass spur was used by one of the

gentry. The iron spur with a five-point rowel was probably covered with

silver or gold gilt as fragments of this layer are visible today. The

style of this example compares well with those in the British Museum

collection which date from the middle to end of the century. The

appearance of smaller rowels has been associated with the latter half of

the 17th century and early 18th century. The smaller rowel of brass boot spur CgAf-2:230426 (Figure 9) could indicate a late 17th century date; however it resembles boot spurs from the British Museum collection dating to the mid-17th century Although based on only a few samples, it appears that boot spurs were worn throughout the 17th century in Ferry land, kept and recycled with changes in fashion.

Though this paper presents an important costume component of the 17th

century excavated from known context, further research in this area

should include comparisons to both print culture and contemporaneous

paintings. The difficulty of using the burial environment for

descriptions of culture is that not all materials preserve in the soil

matrix. Additionally both paintings and to a lesser extent prints do

alter their contemporaneous material culture likely for the purposes of

propaganda and education.

Conclusion

Finally the status of the high boot spur for the 17th

century further provides evidence of the site at Ferry land

Newfoundland being extremely rich and luxurious. Combined with such

material culture as the tin-glazed earthenware, leaded glass, silk

velvets, silk damask and finer woolens of the new draperies it is a site

worth further research [7,8].

Comments

Post a Comment