At A Crossroads: Queensland Transport in 1924-Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Opinion

This article considers the composition of

Queensland’s transport systems during the 1920s, positing events of 1924

as significant markers in the evolution of transport across the state.

By the 1920s, Queensland’s major transport systems on sea, river, road

and rail, were interlinked and interdependent. The range and rapid

development presented challenges for the construction and management of

efficient transport systems, with the introduction of new

infrastructure, institutions and legislation required at a similar pace

and complexity.

For most of its history, from European settlement in

1825, Queensland’s development was less centralised than Australia’s

other states and territories. Throughout the nineteenth century, coastal

shipping, river transport, roads used by horse and bullock drawn

vehicles and a decentralised rail network enabled the expansion and

development of communities, along with commercial and industrial

enterprises. By 1924, a population of 825,000 had spread over the

state’s 1.853 million km² (715447.2998 million mi²), making

ever-increasing demands on transport systems across its sub-tropical

coastal ranges and swamps, inland plains and rivers that flooded

seasonally.

The introduction of motor vehicles presented

challenges and changes for horse drawn vehicle transport companies. The

last Cobb and Co. coach in Queensland ran from Yuleba to Surat on 14

August 1924. Cobb and Co. coaches began services in Queensland on 1

January 1866, operating to and from the rail lines as they opened at

Ipswich, Grandchester, Toowoomba and beyond. By 1900, Cobb and Co.

operated 39 routes across 7,750 kilometers (4,815.62 miles) of

Queensland, providing transport of passengers, goods and mail. The

company began to diversify before its last coach run, purchasing three

motor vehicles in 1911 to continue some passenger and mail services, and

stores in the towns of Yuleba, Surat, St George, Thallon and

Dirranbandi. With increased competition and the beginning of the Great

Depression, Cobb and Co. wound up its operations in 1929[1].

The transition from horse drawn vehicles to motor

vehicles was not straightforward or final in all circumstances. For

some, especially those in regional areas, insufficient access to

services, inadequate roads, and periods of increased fuel costs or

shortages, meant that horses and bullocks were still in use for years to

come. For example, the last Queensland horse mail run, that serviced

Coen, north-west of Cookstown, did not finish until 1951[2]. Further,

although motor vehicles quickly proved more efficient than teams of

horses, carrying goods and passengers over greater distances at greater

speeds, horses remained a sentimental favourite. With the final services

of Cobb and Co. approaching, numerous newspapers published nostalgic

articles about the service. William Muggridge’s poem, ‘The Days of Cobb

& Co.’, concluded that ‘The railway train and the motor-car have

hustled the coach away’, but his toast to ‘The Pass into which the old

days go’ indicated a popular opinion that the former transport service

would not be forgotten [3] (Figure 1).

Having opened its first line in 1865, by 1924

Queensland Railways had almost 10,000 kilometers (over 6000 miles) of

line open for traffic. In 1924, the North Coast line was completed,

providing an unbroken rail connection between Brisbane and Cairns, and

that year a general increase in rail passenger, goods and live-stock

traffic was attributed in part to greater population and‘an abnormally

good season’ for agriculture in North Queensland[4]. Although 1924 was a

year of records for cattle transport, economic challenges in

maintenance, union strike action and decreased passenger numbers began

to place strain on services, and an increase of rail freights and fares

that year was widely criticized by business and community groups.

In his report for the year 1924-1925, Commissioner of

Railways, J W Davidson, identified a “disadvantage under which

the revenues of the Queensland Railways suffered in comparison

with other States because of tapering of rates and fares for the

extremely long haulage of good and passengers” [4]. Davidson

cited the greatest distances at that time by rail from the capital of

each state for comparison, with the longest, almost double that of

any other state, being Brisbane to Dajarra, Western Queensland,

at 2,275 kilometers (1,414 miles). The following year, Davidson

concluded that “While a considerable proportion of the falling off

was attributable to cessation of traffic during the railway strike,

and to the drought prevailing, the rapid expansion of motor

traffic is also responsible for loss of business to the railway” [5].

Motor vehicles were first imported to Queensland during the

early 1900s. Initially their expense and rarity limited their use

to those who could afford the time and money, but by the 1920s

a broader range of the population were purchasing and using

motor vehicles. Following the introduction of the Main Roads

Act in 1920, motor vehicle registrations were managed by the

newly-formed Main Roads Commission. By June 1924, 25,052

cars, 1,624 trucks and 4,563 motor cycles had been registered,

signifying that cars were “being put into commission almost as

fast as they were being imported” [6]. By the end of the decade

Queensland’s agricultural produce, livestock and population was

increasingly conveyed by motor vehicle.

The only real challenge to the increasing impact and

dominance of motor transport was that posed by the

development of aviation in Australia after the First World War.

The 1920 Air Navigation Act designated airfields, standardized

aircraft registrations, and called for tenders for airmail carriage

under government subsidy on four initial routes that would

complement existing rail services, including Charleville to

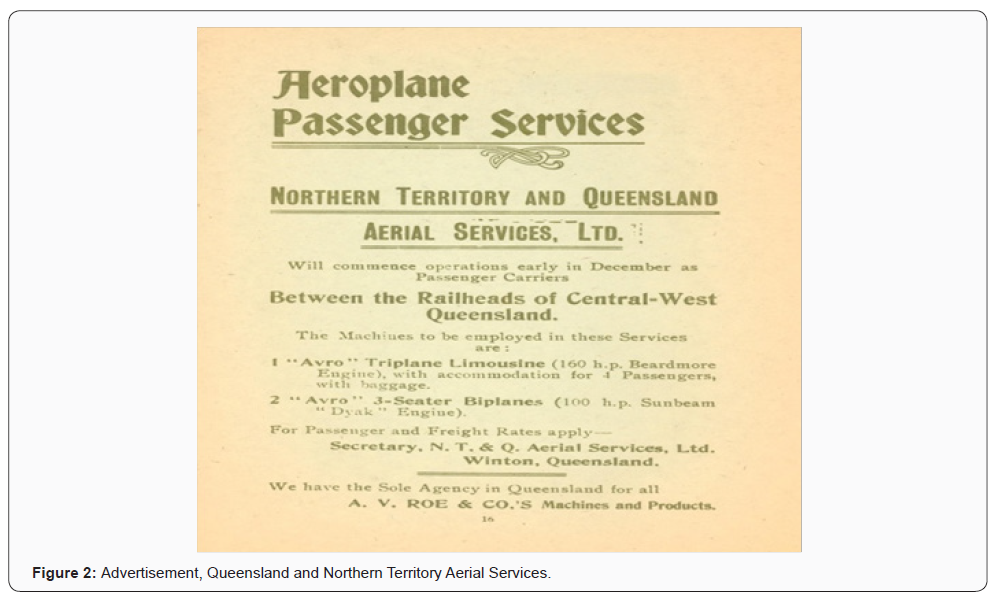

Cloncurry in western Queensland. On 16 November 1920, the

Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd was

formed, making its first scheduled passenger and mail flight

under the subsidy on 2 November 1922. Soon known by its

initials - QANTAS - in December 1924 the company reported that

it had successfully flown over 200,000 miles “without injury to

passengers or staff” [7] (Figure 2).

In 1924, Qantas introduced a four-passenger de Havilland

DH50 on the Charleville to Cloncurry service, the first with an

enclosed passenger cabin. By chance, Prime Minister Stanley

Bruce was one of the first to passengers to promote the service,

becoming the first Australian Prime Minister to use air travel for

an official journey in November 1924. At the end of his journey,

Bruce stated “The good progress which has been made up to

the present and the excellency and efficiency of the services I

have just utilized augur well for the future of aerial transport

in Australia” [7]. Two years later, Qantas began manufacturing

a small fleet of DH50 aircraft, adapted for Australian conditions,

and in 1928 Qantas’ DH50 VH-UER was renamed ‘Victory’

and leased for service to the newly established Australian

Aerial Medical Service (later the Royal Flying Doctor Service).

By the end of the decade, Qantas had expanded its services to

Commonweal, Mt Isa and Normanton, built a hangar in Brisbane

and opened the Brisbane Flying School [8].

Changes and developments in Queensland’s transport

systems during the 1920s represented a unique range of

complexities and opportunities across road, rail and sky,

especially at their points of intersection. The state enjoyed

increasing choice for travel and freight, and by the end of the

decade had witnessed widespread transitions from horsepower

to motor power, and regular air services that could convey

passengers and mail faster and cheaper (in some cases) than

rail. Almost 100 years later, with increasing interest in alternate

fuels and technologies and integrated transport systems, it is

likely that another decade of similar change and development

will soon be part of Queensland’s transport history.

Comments

Post a Comment