Mesopotamia 2550 B.C.: The Earliest Boundary Water Treaty-Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Mini Review

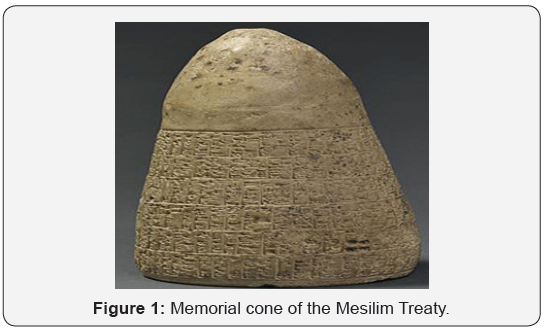

Mesilim [or Mesalim, born ca. 2600 B.C.] was the

ruler of Kish, a kingdom north of Lagash and Umma, which held a

traditional ‘hegemonic’ position in the loose alliance of small

adjoining Sumerian city-states in the region between the Tigris and

Euphrates rivers, south of what was to become Babylon [4]. Because of

the prevailing precarious rainfall conditions, the agricultural economy

of the entire delta area has always been crucially dependent on

irrigation [5], mainly from the ‘great Tigris’, through an elaborate

system of canals and levees which inevitably require close

inter-community cooperation. The geographic focus of the bilateral

Lagash-Umma agreement, concluded under Mesilim’s authority as external

arbiter, was the fertile Gu-edena valley, roughly ten by four kilometers

wide and irrigated by Tigris waters from a canal named Lum-magirnunta

(probably the modern Shatt al-Hayy) on the border between Umma and

Lagash, with boundaries marked by stone steles.

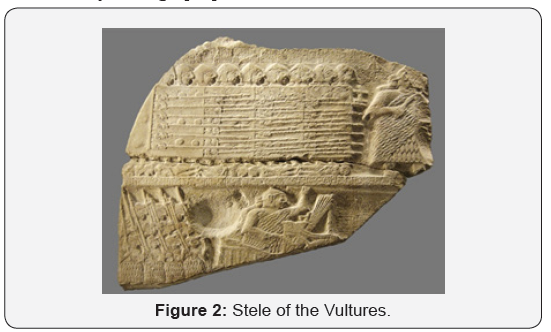

Part of the treaty was a crop-sharing arrangement for

a portion of boundary land (some eleven square kilometers) downstream

on Lagash territory, that was cultivated by Umma under lease, against

payment of an annual rental fee (máš, calculated in silver-shekel

equivalents of barley crops) to cover the costs of canal maintenance

[6]. However, when Umma repeatedly refused to honor its accumulated

tenancy debts, hostilities broke out, resulting in partial destruction

of the canal and in unilateral diversions of water upstream. In several

successive military confrontations (‘the first known war in

history that was, in essence, fought about water’) [7], Umma was

ultimately defeated by Lagash (first under the leadership of E’anatum,

ca. 2470 B.C.; and later under his nephew Enmetena, ca. 2430 B.C.) [8],

and was forced to accept the reconstruction (and extension) of the canal

and the reinstatement of the boundaries as originally drawn up by

Mesilim.

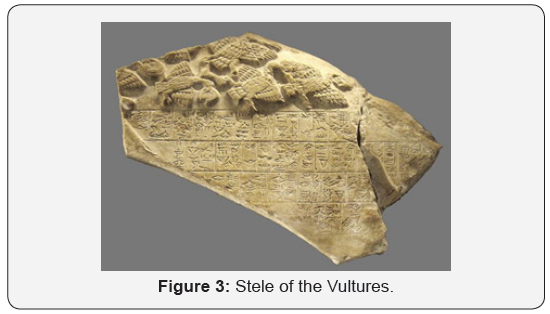

Alas, the treaty so renewed and ‘writ in stone’, and

the peace so re-established, does not seem to have survived for long,

and was eventually overtaken and mooted by external political events

(the Akkadian/Sargonic invasions) in subsequent generations. Even so,

the agreement has been hailed as ‘the first international arbitration’

[9], and as ‘the oldest treaty of which there is a reliable record’

[10]. It remains a unique early attempt at resolving a dispute over

boundary waters by formal reference to a superior spiritual order (in

this case, the deities of both parties, repeatedly ‘sworn to’ in the

text), and hence may indeed

qualify as a precursor of international law in this field – well

over 4,000 years ago [11].

Comments

Post a Comment