Indispensable Knowledge of Eclampsia for Archaelogists and Anthropologists-Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Introduction

It is of great paradox that, besides medical

scientific journals, in general science (and even in general press such

as feminine magazines for example), very few is written on the plague of

human reproduction which is eclampsia (and pre-eclampsia). Yet, these

diseases are responsible of ap. 50,000 maternal deaths worldwide each

year (among some 135 million human pregnancies annually) [1] and

infinitely much more human neonatal deaths, notably in poor countries.

For example, in a recent study in the University

maternity of the capital of Madagascar, there were during a 8-months

follow-up 145 cases of preeclampsia of which 65 (45%) ended in eclampsia

(epileptic seizures “grand-mal”) with 7 maternal deaths of young women

(24 to 34 years of age), and among eclamptics 40 (61%) neonatal deaths

[2].

This discretion is mainly due to the fact that since a

century now [3] Eclampsia/Preeclampsia has been considered as “a

disease of theories”. As a matter of fact, to date the etiology of this

human reproductive disease (and uniquely human, there is no real natural

animal models in the other some 4,300-mammal species, including

primates or great apes) is still unclear, even if we have done great

progresses during the last century

[4]. Eclampsia/preeclampsia belong more generally to the hypertensive

disorders of pregnancy which affect some 10% human pregnancies (and

disappear after delivery), of which 3-5% of total pregnancies complicate

with preeclampsia i.e. organ involvement being explained by one central

theme ‘endothelial cell dysfunction’: kidney injuries

(Glomeruloendotheliosis, proteinuria), liver endothelial inflammation

(HELLP) and the endothelial cells involved in the blood –brain barrier

(convulsions-eclampsia, occurring in ap. 1% of human births if we let

nature do without medical interventions). There are some 6 million

preeclampsia worldwide per year, of which ap. 700,000 end in eclampsia.

To date, the only definitive treatment is delivery, and we have made

almost disappear eclampsia (convulsions) in developed countries at the

extreme cost of delivering knowingly and voluntarily often premature or

extreme premature babies who have to be cared in intensive care neonatal

units. Eclampsia occurs typically at the end of pregnancy in young

primiparous mothers and in half of cases before labour [5].

Convulsions represent a dramatic event that evidently

catch the attention to the point that it has been reported since the

beginning of writings 5,000 years ago (3,000 B.C.) In all continents. In

this frame, specifically grand-mal seizures occurring during delivery,

have been as such reported in Atharta

Veda/Sushruta (India), Wang Dui Me (China), Egyptian Papyrus

(Africa), Galen-Celsus-Hippocrates (Europe) [4,5].

Interest for Archaeologists

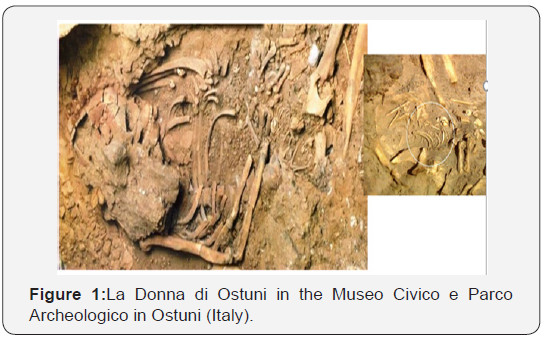

“La Donna di Ostuni.” In 1991, Professor Donato Coppola,

an Italian paleontologist, discovered near Ostuni (fortified

medieval city uphill between Bari and Brindisi, on the southern

Italian Adriatic coast) the skeleton of the human “most ancient

mother” ever found, as accepted by all the paleoanthropological

community with a 8 month-baby in her uterus. These skeletons

were found in the cave “sante Maria d’Agnano”, very close to

Ostuni and they are now exposed in the Museo Civico e Parco

Archeologico in Ostuni, [6] (Figure 1). The carbon-dating of these

human remains are estimated at approximately 28,000 years ago

(MAMS 12903, calBC 26461-26115, calBC 26616-25966 B.C)

[7]. The 20-year-old mother (all her teeth in good shape) and

the baby died together, the foetus of 8 months gestation (45 cm

of length) in cephalic presentation showed an extrapelvic head

therefore not yet engaged confirming that the event occurred

before labour. We proposed recently that the cause of these

maternal –fetal deaths may indeed be due to eclamptic fits [8].

There are apparently 2 other locations where foetuses were also

found inside their mother’s pelves: Nazlet Khater (Upper Egypt)

and possibly Nataruk (Turkana Lake, Kenya).

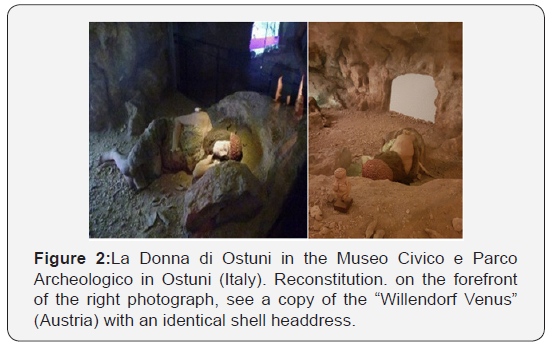

considered as an evident collective effort for a complex ritual

operation, a kind of divinisation of a woman who died during

pregnancy [7,9]. The mother was buried lying on her left side, in

a crouched position, with her right forearm obliquely placed on

her abdomen, her face looking toward the east (Figure 2). A very

interesting detail is that this young mother wore a 600-shell

headdress (Figures 1 & 2) exactly identical to that found on

the “Willendorf Venus” (dated 22,000-24,000 years B.C.) In

Austria en 1908, 1000 km up north of the area of Ostuni. Why

our ancestors have felt the “necessity” for pregnant women

to wear such a headdress? For sure, mankind had since the

origin noticed that there were a “Damocles sword” upon every

pregnant women, and especially young primiparae, namely that

at the end of pregnancy, she could have convulsions and possibly

die near delivery. This has certainly terrorized our ancestors,

and certainly also, seizures were recognised to start from the

head (muscle contractions, visual disturbances, unusual head

or eye movements, mouth alteration, loss of consciousness)

therefore we may propose that the headdresses, or necklace

amulets, that pregnant women wore were probably protective

artefacts against these ominous events like death at birth and

convulsions.

Joseph Szombathy who found the Willendorf statuette

proposed the term of “Venus”, and this name became the standard

for all these feminine artefacts [10-12]. Since 1864, some 250

paleolitical “Venuses” have been found all around the Eurasiatic

area, some of them wearing also headdresses, like “la Dame de

Brassempouy”, “Laussel” in the south of France, the “Venus of

Kostienki” and “Avdeedo” in Russia and Siberia, possibly also

the “Venus of Parabita” [10,11]. Many of these statuettes were

very small and light probably used as necklace amulets. All

the feminine figurines might not have been “Venuses” (sort of

suggestive sexual artefacts) but rather “Maternas”, protective

devices during human pregnancies, also against the terrible,

unpredictable and frightening convulsions.

Interest for (Paleo) Anthropologists

It is well established now that a major trigger of

preeclampsia (occurring only during the last trimester of the

human pregnancy) is linked with a defective placentation at

the beginning of pregnancy. As a matter of fact, humans have

a natural very aggressive trophoblastic invasion (1/3 of the

maternal uterine wall, including the muscle-myometrium). A

defective placentation during the first trimester of pregnancy

may lead to eclampsia/preeclampsia. Among primates, the

haemochorial placentation is linked with the size of the fetal

brain [12,13]. Palaeoanthropologists may refer to the debates

on the subject concerning eclampsia/preeclampsia [4,14-16]

on the different species of hominids and humans. We may then

speculate that eclampsia should have existed in Homo erectus,

Homo neanderthalensis as well as in Homo sapiens, and probably

not in Homo or hominids with lighter fetal brains.

For anthropologists/ethnologists, there is a poorly explored

continent which is the knowledge and/or interpretation of

eclampsia in different human communities, especially in human groups having still not access to effective modern medical and

obstetrical cares (unfortunately, to date, still a majority of

humans). Studies have been made in Nigeria [17], Mozambique

[18], Pakistan [19] and India [20], but it should have a lot to do

further in the future: asking the simple question “what is the

cause or meaning of convulsions during pregnancy in young

women” to women themselves, but moreover to matrons,

healers, community health workers, shamans etc… Tales, myths,

different allegories or interpretation on the subject may be a

millennial culture which could make us approach how our far

ancestor could themselves explain this event. Sending students

or post-Doctoral fellows in different parts of the world should

probably reveal many surprises for the different interpretations

of these fatal convulsions in young women.

Conclusion

Archaeologists and anthropologists must be aware of the

existence of this spectacular and frightening complication of

human reproduction which is eclampsia [21]. Any woman, even

illiterate, has obligatorily heard about it (as it could happen to

her). Having this cultural background may help to understand/

interpret some clues (paleolithical statuettes, parietal arts).

Comments

Post a Comment