Co-Evolution of the Willow (Genus Salix) and Humankind with Particular Emphasis on Estuarine and Delta Systems-Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

Introduction

The willow (genus Salix) thrived in the floodplain environment since the upper cretaceous period, e.g. fruiting Salix catkins were found in the Pipe Creek Valley, Dakota (Figure 1). The life history of Salicaceae is closely related to riverine habitats. Therefore, characteristic traits have evolved. Efficient seed production is followed by establishment on exposed riverine sediments and fast growth. High bending capacity and breaking resistance make Salix shrubs and trees resilient to river currents and waves [1], erosion and sedimentation processes [2]. Moreover, plant parts resprout vigorously after fragmentation by physical disturbance and flooding [3].

Ancient civilisations developed settlements along major flows. Willows naturally occurring in floodplains were used for dwellings along the Euphrates more than 10.000 years ago and for construction, tool handles, hoes and ploughs during the dynasty of Ur in Mesopotamia [4]. Willows provided flexible twigs and branches for furniture, fences for shelter, and fish traps. Willow baskets for food, supply and for storage may have been among the first articles manufactured by human hunter-gatherer communities [5]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO [4] highlights willows as “Trees for Society and the Environment” serving humankind since the dawn of history.

Global Distribution

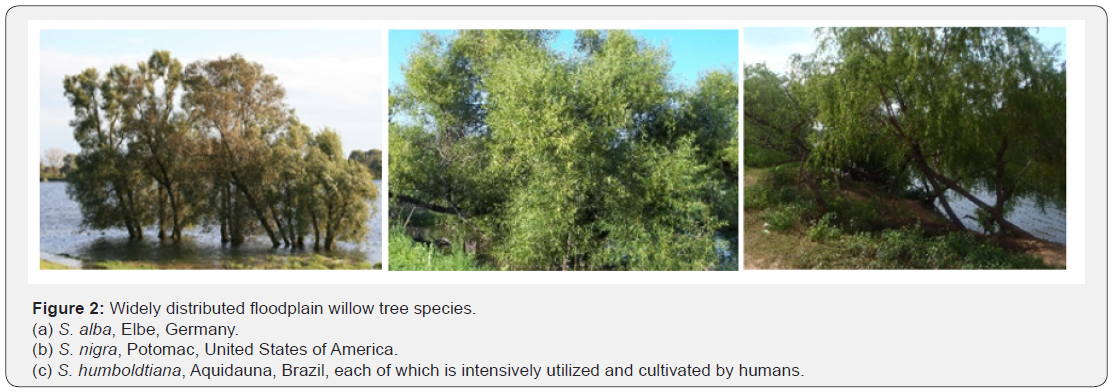

Salix is a globally distributed species rich genus that can be divided into two ecological groups, (i) non-alluvial species of forest, rocks, wetlands with stagnant water and prostrate shrubs of tundra and alpine habitats, and (ii) narrow-leaved alluvial tree and large shrub species adapted to floodplains used for their flexible shoots [6]. The largest tree Salix species belong to the widely distributed and cultivated willows of the floodplain environment (Figure 2). The white willow (Salix alba L.) forms softwood floodplain forests throughout Europe up to North Africa, Asia Minor and western Asia, and is worldwide planted near human habitations and on riverbanks. The Black willow (Salix nigra M.) forms extended forest stands along large rivers in North America, whereas S. humboldtiana W. is the only Salix species native to South American floodplains [7]. Salix phylogeny is complex due to frequent interspecific hybridization. Hybridization accompanied by polyploidy likely played a major role in modern Salix species evolution in genetically variable populations in disturbed floodplains and in cultivation [1].

Estuarine and Delta Systems

In South America, S. humboldtiana settles on non-tidal sandy deposits up to where the lower Parana Delta propagates in the Rio de la Plata estuary. Estuarine islands have been subjected to land use change since decades and today willow-plantations cover extended tidal freshwater wetlands [8]. Tidal freshwater wetlands were occupied by humans since they developed in coastal plain estuaries during the last 6.000 years. Ports were established because these sheltered locations were the most inland point in the estuary that could be reached by ships and where river discharge prevents salt water intrusion, but flat topography allows tides to determine the geomorphology and hydrodynamics [9].

Along the US Atlantic coast, downstream located oligohaline marshes were transferred into tidal freshwater forested wetlands due to colonial land clearance 300-500 years ago shifting sediment into tidal wetlands, resulting in increased accretion. More recently, tidal freshwater forest declines due to tidal inundation and increasing salinity from sea level rise [10], e.g. in the Mississippi Delta where the Black willow forms extended forest stands. Similarly, S. humboldtiana may be substituted by some ten-thousand hectares of tidal forest plantations consisting of hybrid-willows (S. alba and S. babylonica L. (syn. S. matsudana Koidzumi) genotypes exist in the Rio de la Plata Delta. Salix babylonica grows originally in sandy river valley depression in arid-semiarid regions of China with pendulous branches. The weeping willow is one of the most widely used tree in horticultural and environmental application [7] eventually due to adaptation to changing water levels.

North Sea Region

In the North Sea Region, vast tidal freshwater wetlands containing willows still occur along the Scheldt, Belgium, the Weser and the Elbe, Germany, in De Biesbosch and along the Oude Maas in the Netherlands [11]. Most European TFW were utilized by humans for similar reasons as in North America due to the availability of water, nutrient-rich soils for agriculture and the abundance of fish, shellfish, mammals, and plants for food and shelter. However, humans may have also been negatively impacted by flooding and mosquito-borne diseases [9]. Willows extract large quantities of water due to high evapotranspiration rates (phreatophyte-type of vegetation), and from historical references it is reported that willow plantations in malaria affected areas were the most effective for drying up the earth and thus sheltered human settlements [12]. The pulverized bark of Salix alba is even said “its having the properties of the Peruvian bark” and similar effects on “the agues” [13]. The “Marsh-Fever” occurred in brackish coastal and estuarine areas in North-West Europe connected to the occupational history. These areas were exploited by Ertebolle and Swifterbant people since the 5th millennium BC. Subsequent sedentary communities utilized fertile marshes and estuarine forests for pasturage and agriculture. The coastal malaria vector Anopheles atroparvus found hibernation chances in human settlements, stagnant brackish water provided sites for breeding in oxbow lakes and health risks increased in embanked polders with high-days from 1500-1750 AC [14].

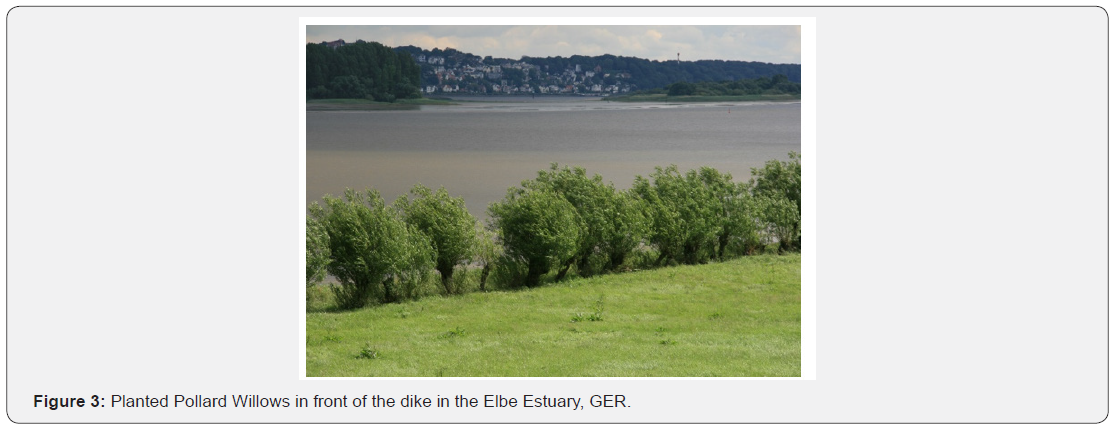

Severe storm surges damaged dikes during that time. This lead to dike reinforcement along the Elbe estuary whereas pollard willows were planted along the dike for protection against surge and ice-scour (Figure 3). The willow plantations led to sediment accretion and prepared the foreland for the use as meadows and pastures. In addition, willow rods were harvested, used for fascines and groynes, and since 1800 until 1950 an extended willow culture for basketry, furniture is reported for most of the Haseldorfer Marsch [15], one of Europe`s largest tidal freshwater wetlands. However, after a major flood in 1962 a new constructed dikeline lead to the loss of approximately 75% of the former TFW area in the Haseldorfer Marsch. De Biesbosch consisted of approximately 8,000 ha TFW but lost vast areas due to the construction of a storm surge barrier. However, still more than 1.500 ha TFW exist including bulrush (Bies = Dutch word for bulrush; Bosch = bush) at lower and willow forests and coppices at higher elevations [11]. Bulrush and willows enhance sediment deposition and floodplain landform construction controlling ecosystem changes in space and in time [2]. Thus, creation of vegetated tidal wetlands in suitable locations for ecosystem-based coastal defence is recently proposed as an economic and ecologic supplement to conventional engineering [16].

These findings suggest that the floodplain willow is not only key resource and develops floor for life but evolves valuable and characteristic traits due to human cultivation what leads to the call “Make me a willow cabin at your gate” to implement tidal willow forest plantation and restoration [3].

https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/GJAA.MS.ID.555673.php

For More Articles in Archaeology & Anthropology Please Click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

For More Open Access Journals In Juniper Publishers Please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

For more queries Juniper publishers please click on: https://www.quora.com/Is-Juniper-Publisher-a-good-journal-to-publish-my-paper

Comments

Post a Comment