Generation Windrush: diasporic landscapes and settlement-Juniper Publishers

Archaeology & Anthropology- Juniper Publishers

The Windrush scandal

In April 2018, the British government faced

widespread public anger and outcry against, and later acknowledged, the

mistreatment of hundreds of British Caribbean residents who had settled

in the United Kingdom following the Second World War [1]. Migrants from

the then British colonies in the Caribbean had been encouraged to cross

the Atlantic by the British government and industriesand were offered

work permits to help re-build an economy and society decimated by war.

West Indian migrants arriving between 1948 and the early 1970s came to

be known as the ‘Windrush Generation’, named after the first 492 adults

and children arriving from Jamaica, who disembarked from the passenger

ship HMT Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks, London on 22ndJune1948.

Migrants and settlers from Caribbean societies have

shaped British history and society for centuries, and the transatlantic

Caribbean diaspora has been built up via layered and interwoven social,

cultural, economic and political landscapes of connection

and subtle divergence [2]. The Windrush Generation’s contributions to

the multiculturalism of British life today have been formative and

striking [3,4]. Windrush writers and artists, such as Sam Selvon &

Linton Kwesi Johnson [5,6]- LKJ - have themselves generated a

substantial oeuvre of Black British writing and cultural energy that

lies as much at the heart of British society, as do the economic

contributions of the early Windrush migrant workers and subsequent

generations. Since many children arrived and settled in the United

Kingdom legally via their parents’ passports, the exact number of the

Windrush Generation is not clear, but it amounts to thousands,

reinforcing the quantitative and qualitative Caribbean underpinnings of

British society today(Figure 1).

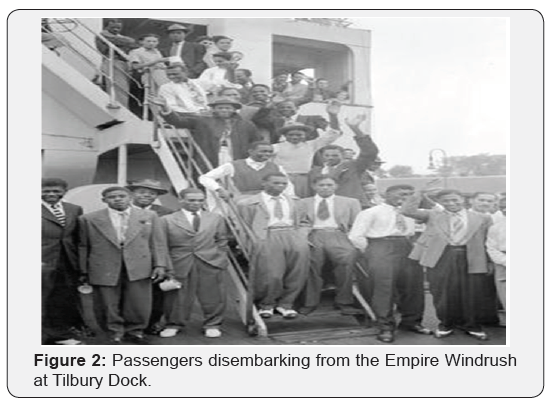

Given that such deep and positive influences of the

Windrush Generation are widely celebrated, it seemed all

the more outrageous and perplexing that since 2012, the British

government’s ‘hostile environment’ policy has created great insecurity

and uncertainty among many lawful British

Caribbean residents. This antagonistic agenda constituted a set

of administrative and legislative measures designed to make

staying in the United Kingdom more difficult for residents without

full citizenship, even if they were entitled to such rights(Figure

2). This proved to be the case for many Windrush settlers and

their children, who have faced restricted access to welfare

services, internship, and actual or threatened deportation back

to the Caribbean, even after five decades of legal residence in the

United Kingdom.

Just as writers and artists such as LKJ and Selvon have

relayed the hardships of arriving and living in Britain during

the Windrush era, and riled at ongoing legacies of empire

and slavery, the current targets of this only recently revoked

crackdown - May 2018 - are now making their own political

and cultural voices heard. New oral and visual diasporic

landscapes of resistance and cries for justice are being formed.

This live topography reflects longstanding tensions of diasporic

landscapes experienced by earlier migrants crossing the Atlantic

in the reverse direction from Britain. Those stressed are felt in

the need to create a new sense of dwelling and self in strange

lands by making fresh pathways, generating mobile identities,

while also collating past memories and seeking stasis and

settlement in place.

Diaspora, mobility and settlement

Disaporic landscapes explore the intimacies between

body and place that mobility continues to create, reflecting

spatial scales of embodiment, while highlighting intersections

of complex identities with diverse historical and physical

trajectories. These embodied landscapes underpin experiences

of migration and settlement, reflecting closely Machado’s

understanding that individual and collective diasporas are rarely

pre-determined, always in motion - ‘there is no road, the road is

made by walking’:

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino, y nada más;

caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Machado’s serial optimism of re-creation and progressive

enlightenment through movement runs counter to more

pessimistic or stressed contexts and accounts of diaspora

formation and memory. Such tensions are reflected in twentieth

and twenty-first century-transatlantic diasporic writings, as

well as many before, en route from Britain to North America.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s experiences as an emigrant to the

United States reflect the more downbeat context of mobility

that can shape sombre realisations and intimacies of footfall

and motion, through troubling or troubled landscapes. While

voyaging across the Atlantic, Stevenson’s thoughts were not of

an open future, but of a lost past and curtailed present: ‘… all

now belonging for ten days to one small iron country on the

deep. We were a company of the rejected… We were a shipful

of failures, the broken men of England’. The historical intimacy

of his Scottish ancestry is subsumed into the hard, momentary

present of a ship’s metal hulk. For Stevenson and many others,

the flight from home, albeit to build another, was not youthful

and full of hope, but engendered a desperate and despondent

setting. Acquaintances were scraped together, rather than

friendships forged. These intimacies of knowledge and

experience, generated by movement, embodied as much distance

as proximity; exclusion and inclusion shared in uneven doses.

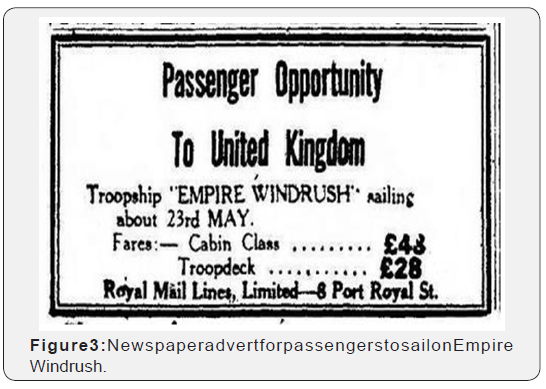

A century beforehand, Johnson [7] had referred to the making

of this new Scottish diaspora in the Americas as a dilution of

energy, a loss of heat from a waning national hearth: …for a

nation scattered in the boundless regions of America resembles

rays diverging from a focus. All the rays remain, but the heat is

gone. Their power consisted in their concentration: when they

dispersed, they have no effect. It may be thought that they are

happier by the change; but they are not happy as a nation, for

they are a nation no longer… they must want that security, that

dignity, that happiness, whatever it be, which a prosperous

community throws back upon individuals(Figure 3).

Traumatic tensions of optimism and pessimism, celebratory

recollection and solemn commemoration of place, person

and movement are revealed. Transdisciplinary approaches to

memory, mobility and mindsets reflect Bergson’s [8] thesis on

spontaneous (la mémoire spontanée) and voluntary (la mémoire

volontaire) processes of recollection. While time, he suggests

runs with a linear, irreversible current, the embodiment of

human memory transcends both time and space. The migrant

and settler’s memory acts vertically, as fleeting, unexpected

glimpses of the past and future that cut across and into present

constructions of place and senses of belonging. Human memory unites past and present in one place, joining or displacing the

individual or collective in the context of the moment and with

intimate depths of human experience, knowledge and identity.

The experiences of ‘Generation Windrush’ are many miles

and eras way from the writing of these two, now celebrated,

Scottish writers. Connections, however, may be found in charting

a series of pathways through visceral and emotive landscapes,

offering the reader and writer a series of routes by which

to figure out diverse memories and narratives of diasporic

identities. The process of creating a path to a place generates the

disaporic landscapes revealed historically and today, and which

are emerging now in poignant new political and cultural forms

as British society as whole comes to terms with the woefully

misguided notion of a ‘hostile environment’. ‘Landscape’ is often

understood as a noun connoting fixity, yet diasporic literature

reveals the word as a ‘hidden verb’:the landscapes are dynamic

and cause commotion; they are ‘bristling’ with identities,

memories and the transformative effects of moving through

place[9-12].

Comments

Post a Comment